Hoarding the Good

A light, frothy essay on having too many useless notes and photos stored on my phone & writing in diaries.

We were all supposed to be Spring cleaning. Hands and knees and elbow grease. Soap suds beading on the kitchen floor. Sweeping over the wooden floors with all their oaken knots and then vacuuming with precision. Vacuuming just like the special lawnmowers used on football fields which leave stripes; lighter green cheek-by-jowl with emerald. Laundering all the bed linen. Flinging the windows open so that the curtain fabric flutters like idle butterfly wings. In steals the natal primavera sunlight, skin-kissing fresh air. Everything is clean and good and new now, fresher than the gambolling lambs wild upon the pastureland.

Unfortunately, I have been busy doing the opposite. Cluttering my life.

Just like a magpie using his pronounced beak to sift through items displayed at a car-boot sale, or through an antique’s shop’s curated wares. ‘I like this,’ he comments with approbation about a shiny box of cufflinks. ‘But this I like even better,’ he says with a sharp intake of breath (the first semi-quaver of a wolf-whistle), sizing up a silvery cigar-case. Recklessly and fecklessly, he will be purchasing everything. His magpie wife at home will not be pleased. Superstitious people (are you one of them?) have to greet magpies when they spot one. They’ll repeat their regional version of: ‘Good morning Mister Magpie, how’s your wife and family?’ ‘She’s giving me the cold shoulder ‘cause I spent all our money on tat,’ Mister Magpie will mutter darkly, and proceed to preen his feathers, anxious to avoid the subject.

Yes, I was supposed to be preparing for the next season of life, tidying things up both literally and proverbially. But I am accumulating and mess-making. For example, there are 20,000 photos on my phone (despite my best efforts to purge them) and insistently every day I am reminded that my ‘iCloud storage is full’. Stand to attention! Do something about it! Mobilise the troops and delete your photos!

Everything I see is special. This is the crux of it.

If everything is special, or feels like it is (and that is surely the same thing?) then to that end, everything deserves to be taken a photo of. I know other people feel this way, too. It softens me to imagine my favourite old-timey poets with cameras. Those who have been dead and sundered in their coffins some two centuries or more. Their bones have long since chiselled into underground arcana; one day awaiting archaeological excavation alongside coins or fragments of earthenware. Yes, I imagine these poets, our old guard, delighted by the idea of a camera—let alone the niftiness of a portable camera-phone! Don’t you think they’d have loved it; the sentimental novelty of it? Flick through Wordsworth or Shelley’s camera rolls in April and you will be confronted by hundreds of nearly identical photos of daffodils. But I imagine that every daffodil they saw would have felt special—precious—to them. And so they all required photographing.

Similarly, on the subject of digital clutter: the Notes app. I have in excess of 1,400 notes on my phone. There is everything mired away in there, a miscellany:

Poems. From my younger years; I dabbled then.

Nice things people have said to me—or nice things I have overheard being said to other people.

Text drafts, and, for that matter, more serious email drafts.

Shopping lists. Mainstays of fruit, vegetables, yoghurt, milk. Coffee.

Passwords. (For we must be practical, too.)

To-do lists, much in the same spirit. Many from my university days. Which libraries to pillage and which books to scout like an erudite sniffer-dog, when to hoover my room, when to refresh my bedding.

Ideas for essays. These lists resemble graveyards, or palliative care wards.

Mistyped (for typed in haste) exchanges of dialogue for my novel. Eureka moments of devising the plot.

Thoughts which would amuse no one but myself, or engender only polite titters were they to be broadcast.

Extended Mind Thesis is the scientific principle of notebooks.

Or thereabout. It is the theory that we increase the quantity of ideas we can remember by writing things down, because then we do not need to rely on our (unhelpfully fallible) memory.

Unwittingly, you will make use of this thesis everyday. Post-it notes stuck to your laptop screen. Reminders scrawled on the back of your hand in pen ink. Notes affixed to the refrigerator with magnets. Plump Google Docs files or hefty Microsoft Word documents, chock-full of lecture notes.

We need only glance down at the paper in front of us, and read the equation or the new piece of vocabulary, which we had forgotten but are now reminded of. A mind like a colander, speckled full of holes.

The above is an edition of the seventeenth-century philosopher John Locke’s book New and Easie Method of Making Common-Place-Books—alternately titled between prints and translations (it was initially published in French, and sad English monoglots had to wait two decades to finally discover what wonderful new method Locke wanted to tell them about.)

This book is essentially a revision guide.

Just as we teach students of exam-taking age how to optimise their time spent studying with odd fad-like ideas—write in blue ink! Listen to classical music! Chew gum! Try the ‘Pomodoro’ study method! Lock your phone away! Lock yourself away! Alternatively, lock your family away lest they distract you! Certainly lock your girlfriend away, useless needy bastard. Et cetera. YouTube ‘studyfluencers’ make a mint out of telling you how they got their A grades and how you can too.

Most industriously, Locke had spent 25 years figuring out what was the most efficacious method of note-taking. He was the original proponent of the work smarter, not harder philosophy, so to speak. Scholars of all varieties (physicians, natural philosophers, lesser-spotted humanists or theologians) could flick back through their work in overview of their expansive knowledge. This process might seem quite intuitive to us moderns, but then again, everything needed to be invented once.

When my classmates and I were studying our Shakespeare paper two years ago, we had a wonderful tutor who commissioned us all to:

a) Firstly read every single one of Shakespeare’s plays (obviously).

b) And then to compile our own commonplace books, noting down thematically-arranged quotations which struck us. Ever the romantic, I mostly paid attention to phrases and conceits appertaining to love somehow. I still filled a whole notebook, though.

c) Tertiarily, we would also feel like real seventeenth-century scholars—as if we were reading Shakespeare at the time he was being published—by seeking to emulate their note-taking practices. Entering into the habitat of the literature we were reading.

A practice of recording everything we found striking or beautiful; a treasure trove of precious things.

Probably very many metaphors could be used to characterise our minds.

Try this for size: Is your mind like a library?

Certainly, we have absorbed some metaphors of categorisation into our language usage already. On our phones, we store photos in a ‘gallery’.

My phone’s photo gallery has no room left. How did I let it get like this?

There are far too many screenshots, to begin with. Everything sweet or witty or comforting that my friends think to message me—bagged, labelled, inventoried. I screenshot it all.

Almost every pretty tree or blossom I have passed on a walk in the past few months, I have taken a photo of.

Similarly: a cat I met on the street, gently nuzzling my ankles, wending its way between my calves? I stoop to conquer; bend down to give it a stroke. May I take your photo, little beast?

My friends grinning behind a cup of coffee. The way the dress my mother is wearing moves as she strides out ahead of me. A particularly charming cottage façade, smothered by wisteria. A toothsome salad I made. A recipe I found online of an equally toothsome salad I hope to make.

It all feels so important to me. That photo (or five) of the swaying bluebells—it’s not entirely about the bluebells, but what is in the photo (and what no one else but me can discern) is how I felt whilst looking at the bluebells. The peace, the victory, the triumph, the recollection—pictures of nostalgia; pictures of a hoped-for future. All descended upon me, quite unbidden, in study of the bluebells. That is what the silly, amateurish photo represents. You see I can’t just delete it. How impersonal a death.

I have my scattered prolificacy in my notes app, and I have my tens of thousand sundry photos. Everything is clung on to.

In my university bedrooms, which are the only times I have ever had a bedroom all to myself since I was seven years old, the only decor I brought with me were my bedding, my books, and best of all: my letters, cards sent to me, and my photographs. Heaven forfend anything else beyond this, with the exception only of flowers bought (the sweetest stillborn luxury I know), and imports of library books, too precious to be consulted only once over.

Friends and guests laughed at my room, for I suppose it was quite bare. Although I loved it. My third-year bedroom was the smallest and by far my favourite. Big sash window out of which I would call down to my friends as they walked by the house. Pinboard unto which I stuck festival wristbands, good luck cards for exams, old birthday cards with pretty designs emblazoned on the front. An ever-changing vanguard of flowers divided between old jam jars and drinks tumblers, temporarily substituting in as vases.

When the flowers inevitably died, even after a long life, I’d press them. (‘He had a good innings,’ as we say when an octogenarian shuffles from this mortal coil.) Between paper towels, sepulchred under stacks of books like Grecian colonnades.

These were the things I could not let go of.

For my love of precious ephemera (a logical contradiction, shush) is checked and balanced by my hatred of clutter.

Essentially, I don’t like THINGS. I like rooms to be tidy and not over-filled. If you must decorate a room, do it sensibly and with temperance, restraint. Decorate a room through your choice of paint colour, through the art you hang on the wall (this ought to be art you actually like, even if it’s only a £10 reproduction print with an imperfect pixel resolution, not art which the home section of a supermarket decides is suitable for a living room wall). Decorate your space through the fabric of your sofa (and if it’s a free Facebook marketplace find, which you enlisted a dodgy man-with-a-van to lug to your front doorstep and is covered in awful faux leather, then you can reupholster it!) and the cushions you place atop it, and the simple vase of wildflowers on the coffee table.

For the love of all good things (hah), please no ITEMS. No PARAPHERNALIA. There is a word which should not exist, and that word is objet—ie. object without the ‘c’. What this word denotes is an item which has no purpose but decoration. (Or, more truthfully, collecting dust and being difficult to transport when you move house.) Don’t worry, I hate useless gadgets as well. I am indiscriminate in my loathing for unnecessary items, the adjuncts of everyday life. Stop being such a weakling—you do not need a specific ice cream scoop which you can only use for scooping ice cream; how often do you even eat ice cream? If you lean your upper body strength into the task, then you can use a spoon to serving your ice cream. There you go, I’ve saved you some space in your overfilled cutlery drawer. (That’s a somewhat extreme stance, granted. Ask me my opinion on sandwich grills, salad shakers, Ninja ‘CREAMI’ machines and such like.)

Items we decorate with should be things we love. Not things marketed as decor, from IKEA or Dunelm or Homebase or B&M Bargains. Do you know what I mean?

Recently I set out on a personal archaeological expedition which took me all the way to the chest of drawers stationed in our hallway.

To my delight, I discovered two old diaries which I had forgotten about, penned from the latter half of 2021 into late 2022: years which I thought I had left undocumented.

This means I now have fifteen volumes of diary-writing extant. I started aged twelve in 2016. These entries are neither witty nor interesting—but I have them, and therefore I retain pleasing evidence that aged twelve I was neither witty nor interesting.

My rules for diary-writing are simple; I don’t have to do it everyday, but I can if I want to. I don’t have to have anything to say. What I do need to do as often as I can, though, is relate things said to me which I loved or made me laugh; create credible likenesses of the people I adore.

What I do most, though, is recount events. Solipsism is discouraged, narration is encouraged.

This, I think, sets me at variance with many other diarists.

What seems to be currently in vogue amongst those who keep a journal/diary is doing inward work, processing your feelings, isolating areas of your character which need improvement. My diary is not an arena of me waging war against my worst self. There are no instances of pastel highlighters being used, no washi-tape, no stickers, no stamps, no enviable calligraphy.

Rather, my diary (as an artefact) is reminiscent of a film-roll of days I have lived through. Who did what, said what, wore what. What gossip? Where did we go? Who did we see?

My diaries are not intellectual affairs. Not by any stretch of the imagination. Alas, alack. They include, as far as possible, transcripts of things said. This I love so much. I love re-reading things said to me, trying to reconstruct the voice and tenor used.

Remastering the sweet nothings in a musician’s studio.

Nothing particularly important ever happens in my diaries—or, by inference, my life. Thank God. The precious things go in, though. Precious but not important in the typical sense. The flowers we saw and who I saw them with. And what he—she—said to me about the flowers.

Thank you for reading!

𓆝 𓆟 𓆞

Addenda (Introducing you to my diaries)—

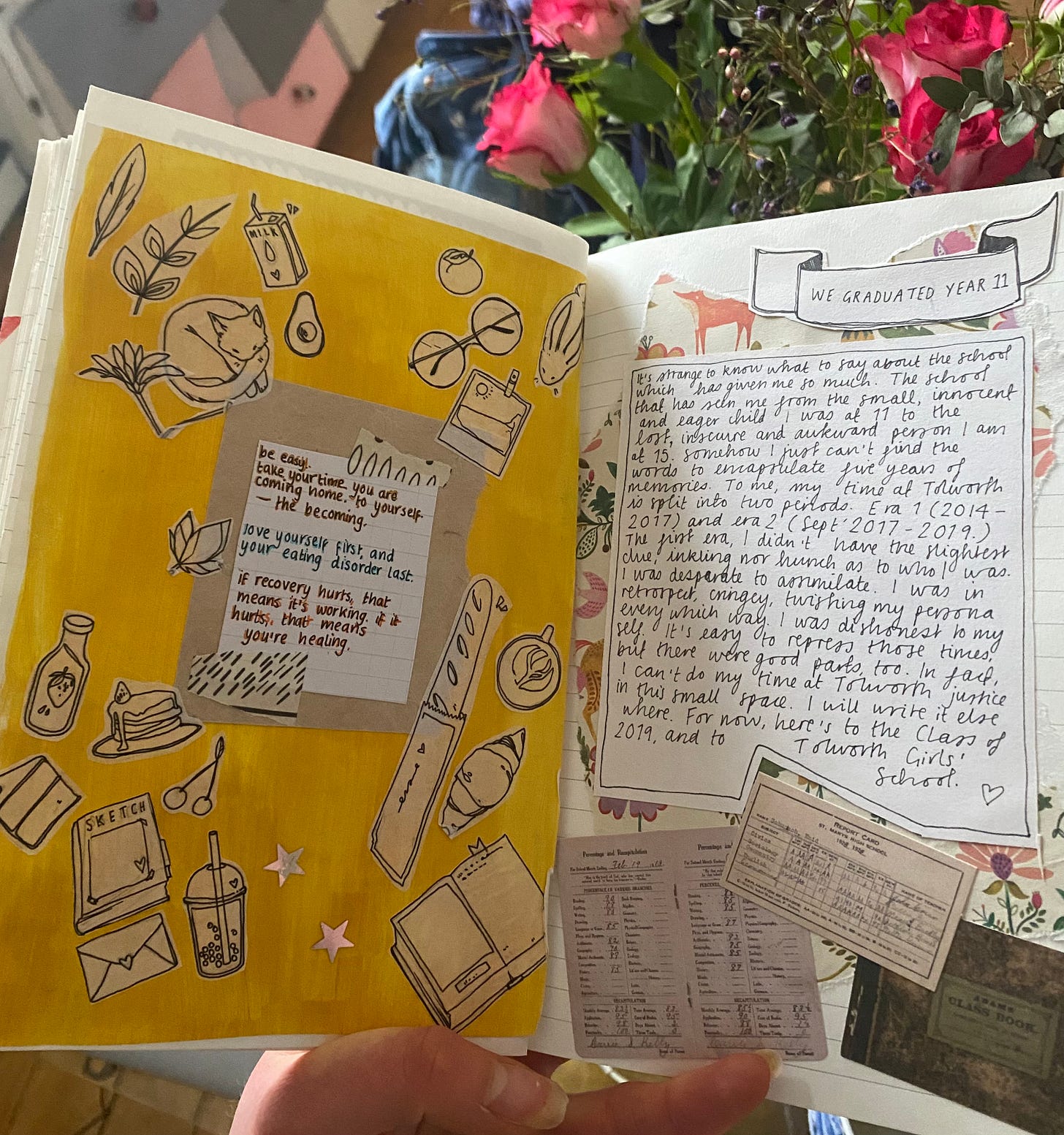

When I was fourteen, I did start a more exploratory journal, into which I tucked tickets and photos and used colours and my imagination somewhat.

But that was very silly and little girlish indeed!

Cover image: (Detail) A Woman Writing With A Quill by Adelaide Labille-Guiard (1749-1803)

brilliant writing as usual! and I loved reading (as seeing - they look amazing!) about your diaries. I've always used journals as an introspective tool and a method for me to cope with various things causing me worry, stress, anxiety, and so have actually found myself journaling less and less recently as I feel a lot better on a personal level. so I think I'm going to take inspiration from this and begin to use my journals like a diary. The idea of recounting events and conversations is wonderful, and honestly, I can't wait to get started now!

This touched something for me and I saw myself in every word of it. Absolutely loved it and beautifully written