Maybe if it makes you sad, you shouldn't think about it?

On finding the balance between acknowledging reality and preserving one's precarious hold on joy.

This one is going to need a small but rabid squadron of disclaimers and caveats to cover for me. What I am not in the slightest sense advocating for is wilful ignorance, ie. with regard to terrible things happening in the world. We need to be caught up, informed, engaged and interested; we need to be feeling for our fellow creatures. The things I am going to discuss in this article—the things I am going to suggest we spend less time thinking about—are things which make us sad for no good reason. Things like worrying about the passage of time, as a classic example. There’s nothing we can do about it. Our sole option is to use our time well even as it trickles slyly away. Meanwhile fretting about the fact that we will never live this day again seems elocutionary on how to waste time.

Which leads me out of breath and conscious of having wasted time with preliminaries and fatuous overtures. Here we go.

My feeling is, from the outset, that sometimes I read heartachingly beautiful meditations on Substack which truthfully leave me feeling quite hopeless, and, crucially, that this hopelessness (both imparted from the writer, and felt by the reader) is unjustified.

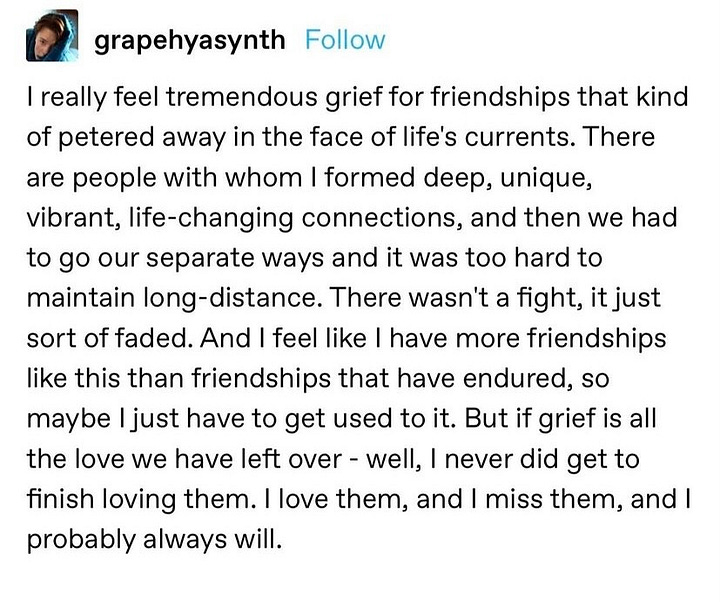

Closing an essay, one is sometimes left feeling bereft; actually, a bit plundered—like my happiness was yanked and torn away from me in the middle of my reading. No! How dare you! Look at the human condition! A sad thing, not a happy thing! Substack—which I am using as a quadrat random sampler (like how you estimate insect populations in a field) for the current literary wilderness in 2024 on aggregate—teems with lyrical essays on sad things. Topics de jour are things like: losing one’s girlhood, wasting the summertime, saying goodbye to someone with the intention of seeing them again in a week’s time—but then that time lengthening intentionally-but-also-maybe-not-unintentionally into forever.

And these topics are sad things. That I can credit. But they are responded to in needlessly sad ways, sad ways which suggest an intense and disarming powerlessness.

Let’s take the last example from my list of topics which current writers are recognising as prescient, as needing to be written about. The idea of saying a nonchalant, unremarkable goodbye to someone and, though they remain alive and so do you (I think), and maybe don’t even live very far, you never see them again. You become strangers—with nothing seeming to have changed. That is the point, though. You never lifted a finger. People sometimes need to be prodded. Sometimes, even though it seems a bit childish people need to feel needed, wanted. (Actually, as soon as I typed that out, I disagreed with myself. There is nothing childish about wanting to be wanted inasmuch as there is something terribly human about it, and I am reminded also that a child is a human—so all of this amounts to the same thing, and the feeling remains an understandable one.) It was not inevitable, that you and this other person fell out of contact, and you were not without agency. You shirked your duty and the only struggle you put up was a feeling of regret that came as an afterthought.

And so I read these absolutely beautiful pieces of prose but I am not left edified by the beauty, for instead I am distraught, in a small way.

Now, a piece of literature should destruct, or at the very least disrupt, you every once in a while. Sad books are important whether the sadness within them is derived from a real, lived anecdote or a fictive flashpoint of plotted anguish. This kind of writing is often shelved amongst the books readers find most relatable: writing centred around grief, loss, breakups, passing through life-changing situations. But (and I grant you that this is no original observation of mine) writers too often to enjoy romanticising things, romanticising their suffering.

Writers sometimes seem to extract only sadness from their experiences and settle for the option of merely writing about things that have happened to them instead of doing something about the things that have happened to them. Okay, you lost a friend. Awful. Stop writing that essay about it, stop sitting there and ruminating on the inkling that things could have gone otherwise! Go and call them! Lie to rest your pride! Then come back, and write your essay.

You may find that you still have all the same sadness stored up in you to write and exercise your poetic prowess in intellectualising this sadness, siphoning it into a little masterpiece and uploading it to the Internet contentedly. But you may also find that you can finish your essay a little differently now. The conclusion no longer needs to be a meditation on the ephemerality (the ephemerality you decide is inevitable) of human relationships, undercut with a hasty remark that, even so, no love given out is wasted. The conclusion may now read more complicatedly: I thought I lost a friend but actually I called them and it was awkward at first because so much time had passed and we are different people now but I told them how much their friendship had meant to me and it touched them. And actually even though their life has changed they loved telling me about it, and catching up on mine, and then we decided that we might as well get coffee next week, and honestly I think I can see this same-but-different, old-but-new girl meaning a lot to me. You said goodbye not thinking it was forever and then it started looking like forever and then it wasn’t forever, not at all. And it’s a much happier ending, and I the reader am moved at the reconciliatory satisfaction of it all.*

I am reminded of that quotation from Ursula Le Guin:

‘The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pedants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting’

I begin to fold, though. Isn’t all this savouring of so-called toxic positivity? It isn’t meant to. Upsettingly, there will be some friendships and relationships which despite our best and most proactive, concerted attempts end only in elegiacal essays.

*An intermission question: how much should taste or aesthetical concern affect the way we live our lives, as though we lived for the autobiographies we were to one day write? This is a similar sentiment to when people on TikTok suggest doing something ‘for the plot’: doing something because it’ll make for an interesting story—or, in this case, a happy and beautiful story. Should we make decisions because we think in twenty years time (or two weeks) it’ll be a beautiful story to recount? I am inclined to say that if we think we will make kinder decisions—the ones which perhaps involve us swallowing our pride, like I said, and becoming the bigger person—then yes.

But, that known, acknowledged, and embraced, I still feel that in our desire to have meaningful things to write, and our socially-diffuse conflation of meaning with sadness, we intentionally live sad lives—sadder than they need to be, I mean—and shruggingly, passively, make sad decisions. This might even be a rather subconscious affair. It might be that we have blearily conceived of the shape of our lives as mournful but inalienably poetic. And, to be honest, I’m not even really sold on my own emergent semi-thesis: that people live sad lives because they want to write sad things, with the enthymeme underpinning this being that sad writing gets clout. It is popular.

And something cannot be popular without having to it a degree of resonance. Things (whether books, clothes, beauty items, or songs) are lifted up and buoyed into trendiness, certainly, but this will surely be because at one stage previously, someone organically liked the thing, and related to it. A discrete thing: even independently of an overactive marketing industry which will try to sell absolutely anything it can to as many people as it can, popular things may have achieved some of their popularity by genuinely speaking to a social issue, a common feeling—seeming to solve or address a want shared by great swathes of people. Which is to say that sad writing does well because many of us, unfortunately, experience sad things, and bond over the sense of kindred collectivity created by a piece of writing about that same sad thing we went through. By sheer virtue of that piece of writing existing and having been authored by someone else other than ourselves we receive conclusive evidence that we are not alone—which either helps you or it doesn’t, but it likely doesn’t leave you feeling any worse.

My point is that the proliferation of personal essays which patently, wantonly, deliberately indulge feelings of sadness to an unhealthy extent is not good. Please stop synthesising anguished emotions in the bid to try and write something which will be recognised as pertinent, relatable. Similarly, we are semi-intentionally creating the perfect conditions for overthinking: a temperature-controlled, fastidiously regulated terrarium of worry. Many of us are anxious beings by nature, I warrant you, but we often do not help ourselves. As writers, we are responsible for the way we structure our writing. We seek to produce responses in our readers—we lead them like a horse from one thought to another, and coax them persuasively to adopt our opinion on something—or at least to flirt with it a bit, have it over for dinner and entertain it hospitably.

We would, it seems, rather do the easier (and more culturally lucrative!) thing of writing about how sad we are this summer, and how sad we are that this summer was ending, rather than write about the little things which we could still reasonably achieve—and our nascent anticipation for autumn, if the remains of the summer were truly unsalvageable. What we write is transferred from our thoughts, and in turn is transferred into the thoughts of our readers. Thus when we share our writing, as so many people thankfully do, we have to accept that we are responsible for the feelings we engender and infect other people with. Providing readers with a sense of consolation and safety—serving as a reprieve and respite for hurting hearts—is a truly commendable vocation. But we need to think about inspiring hope, when we can, too. Leaving an essay on a forlorn and doleful note may be a question of taste. But I would ask that we think about how sad a sad piece needs to be. What actions in our reader can we encourage, what options can we illumine and emphasise for them, if they are already feeling as hopeless as we might imagine them to, having clicked on our essay about such a sad topic?

Even loose, floaty prose has an agenda however muffled or implicit—even if it needs a scalpel to bring it out. The vertebrae of a piece of writing come from a calcified agglomeration of tiny, interconnected thoughts and feelings from the writer. All of this is good, though something to be mindful of. When we express, for example, that summer is inherently sad, are we projecting? I still wonder why, for T. S. Eliot, April is the cruellest month, and why he would have us treat this assertion as axiom. Maybe I do not live my Aprils any differently, knowing that one (albeit influential) poet-person felt this way. But what, I suppose, I am saying, is that sometimes we treat non-sad, or only-a-little-bit-sad, things as cataclysmic, because a piece of tortured writing we read online made it so, because the writer wanted to wear a metaphor they’d come up with in the shower like a new dress. We are often our own worst enemies, and those with a predisposition to either write or voraciously enjoy the writing of others particularly embody this aphorism.

Some things are sad, and our writing on this ought to reflect that. Some things are only as sad as we strive to make them, and our writing ought to reflect that, too—hoping always, the chance of happiness.

*Below I’ve included some screenshots of a post I saw on Instagram (via @sadloveletter on that app) just now which exemplified exactly the sort of thoughts which I think are perhaps beautiful, but also dangerously unproductive, and encourage us to surrender our own agency, and simply (wrongly) accept that things are the way they are, that things have altered and people have left.

I acknowledge I could be labelled as delusional here, but I am willing to face the sentence.

We are not powerless and the line between being delusional and taking wise risks is a fine one.

SUGGESTED READING: This short essay about that intensely brilliant connection that is sometimes sparked between two souls—and how spending years geographically apart cannot destroy it—because we are conscious agents in our relationships just as much as we are subject to the inexplicable laws of connection (eg. why do our souls ‘click’ with some as deeply as they do?). A beautiful read.

Wow! Alice just wow! This was such an unmitigated pleasure to read. At times I felt like you were writing directly out of my own brain but much more eloquently than I think. You are fighting the good fight. Hope is the thing with feathers!

this is such a thoughtful, astute & beautiful essay, clara. i have often had the same thoughts & actually used that ursula k le guin in my own writing because frankly, i’m terribly disgusted with our culture’s life affair with sadness. i can often FEEL sad, yes, but i do not need to BE sad. it’s why i always try to have (where possible and realistic) an upwards trajectory in my writing. wonderful words from you as always 💛💛