Other People's Houses

The privilege, strangeness, and spectacle of visiting someone else's house to play as a child.

When we were all growing up, we could be divided into two categories. For the most part.

There were the children who visited other people’s houses and then there were the children whose houses other children came to. Or to put it another way: it was either your mother cooking other children dinner, or you were the one eating dinners generously cooked by other people’s mothers. In essence: there were among us the benefactors and the charity cases. I’m only joking. A little bit.

The former group’s parents were typically stable, somewhat put together, or certainly good at convincing others that they were. Of course, if we’re being honest then every family has its skeletons in the cupboard. Some families, though, do a better job of keeping up appearances, of tidying up and stowing away all this bony clutter. Meanwhile other families don’t really bother to hide their skeletons away. They leave them out sitting on the sofa for all to see and gawk at. Other children don’t typically come round to play in those houses. The skeletons are not always particularly hospitable. They are prone to saying something offensive or unsuitable for little ones to overhear.

Some children’s houses were very in demand, it felt like. Everybody was trying to weasel their way round or find an in. Like scoring a reservation at one of New York City’s haute restaurants, or bribing a bouncer none too smoothly for entry to one of those clubs which one visits to see and to be seen. (So I am told.) These are patently not the clubs one goes to to neck jägerbombs whilst listening to a nineteen-year-old prodigy’s house set. From GarageBand to London’s Heaven: going up in the world, so we are.

Quite frankly, it wasn’t always clear what scored you an invitation round someone else’s house when you were little. I suppose, quite often, it was more of a reflection of your parents being friends rather than the children themselves—who did your guardian strike a conversation with at the school gates? Was there one clique of mothers forming? The mothers who fed their children only organic foodstuffs banding militantly against the mothers who did not. Playground politics. Sometimes it seemed like parents methodically seized on an idea of who they wanted their children to befriend, and issued calculated invitations to their homes accordingly.

I was always fascinated by the mathematics of reshuffling which seemed to go on in some families when another child came round to play. What would a family attempt to conceal about their normal life? For example, would the mother ask her child to have their room spotless before inviting a visitor into their home, even if that visitor was only seven years old and potentially lacked the discernment to know whether a room had been freshly vacuumed or not? (Although, this being said, some children are the most merciless of judges.) Or would she ensure she’d been food shopping the night before, so that the kitchen was stocked with a plethora of inviting, luridly-packaged snacks chock-full of E-numbers that she would never usually buy? (“You might as well eat poison,” and so forth.) Or would she ask her child to act as a messenger—encouraging them to ferret around and reconnoitre, ask the friend who was coming around what their favourite dinner was—just so that she could make it for them.

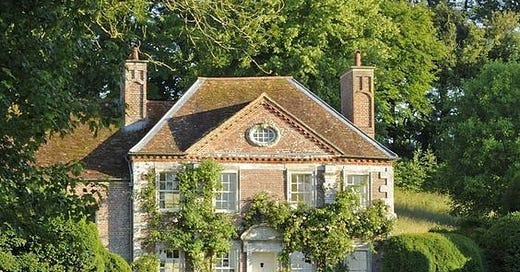

Sometimes, families would make the extraordinary efforts of booking a day out or piecing together an elaborate plan for having one of their children’s friends over. Their mission was to spoil you, and you were indeed going to be thoroughly spoilt. Maybe they’d take you to get ice cream or to a theme park or the zoo or a castle or a museum or a National Trust property (these being invariably solidly middle-class families).

Speaking for myself only, I usually tended to prefer it when families didn’t go to such protracted measures—although of course I treasured the effort that some parents would go to. Parents can be such magic-makers, even when they are worn down to the bone by their jobs, their marriages, monetary worries, their badgering in-laws or their own parents’ precarious, failing health.

But what I really loved was when you got to see the family exactly as they were normally, with all their guards lowered. Maybe they’d pick you up from school in their untidied car: crumbs on the upholstery; muddy football trainers in the boot; dog-eared book on the floor; baby sister’s unwieldy car-seat in the way. And you’d run errands with them; picking something up from the post office or dropping off an important document at one of the parents’ offices, then nipping to the supermarket to grab some last-minute ingredients for dinner. At home with the Smiths or the Joneses, almost as if you’d walked in invisible and unseen. As though a camera crew had stolen in to record the banalities and idle chatter of a family. No pretensions, only ordinariness.

One of the first ways we learn that other people’s families aren’t identical to our own is through encountering them in their own habitats. Entering one of our classmate’s homes and observing how their family moved and loved each other—or didn’t, maybe, seem to love each other in the slightest.

What did other people’s homes smell like? Laundry, cooking, old people? On the flip side: reed diffusers or chemically air-fresheners? How troublesome was it to find the bin in their kitchen—was it cleverly secreted within a built-in counter, or was it a rickety little thing with a temperamental pedal lurking next to the fridge? Did the family own a dishwasher? Did they say a grace prayer before eating? Were there strict rules at the table? Or, further still, was it made clear to you that usually there were strict rules at the table, but that these were being flouted and broken because there was a guest.

Sometimes parents snooped a bit in your life. They liked to know how you were doing at school, maybe—and sometimes not-so-indiscreetly sought to compare their own children to you.

Were you encouraged to break household rules? Did the friend you were visiting encourage you to pillage the cupboards with them and take your snaffled haul to the sofa to be grazed upon? All for a younger sibling with a penchant for whistle-blowing to stumble in and grass on you: ‘You’re not allowed to eat in the living room. I’m telling!’ and the ensuing ‘MUUUUUM!’ (For maximum effect, please read my children with nasal little British accents.)

Indeed it is often baffling for an only child when they first witness siblings bicker and fight. Confounded, they wonder: is what I am seeing love or hatred, or both or neither? How exhausting. The whiplash between truces—just for something to then promptly it all off again. Treaties accordingly ripped up and dismissed, the end of a period of détente and the return of attritive warfare.

But, regardless of their own family dynamic or how many siblings they had themselves, squabbling at the dining table, it was often rather worrying for the visiting child when siblings fought. A bit of an impossible situation. Let’s say you were visiting the house of one of your close friends—your own age, a classmate at school. But they had a cool elder sister and, of course, you wanted to befriend said cool elder sister. How on earth were you supposed to pick a side, were they to lock horns and start rutting, to get into a fight? Said elder sister might try and seek your support to bolster her campaign, believing you to be a fickle and insecure nation-state. But your friend might believe that they had the greater claim to your alliance, and instead set your munitions factories to work producing weapons for them. You were caught in the cross-fire; terrified and staggering in No Man’s Land.

But, regardless of escalating tensions and intra-familial conflict, at the end of the day it was not a dynamic to which you properly belonged. Granted, you were useful insofar as you were a strategic token or perhaps a talented rapporteur. But the conflict wasn’t really about you. Because later that evening you would leave. You were only visiting, just passing through. You would zip up your sensible winter coat, unhooked from the peg in the hallway, and you’d lace up your shoes and your friend would suddenly pipe up and clamour and beg for you to stay a bit longer. And maybe the mother would waver, but even a generous extra half-hour wasn’t the same as you belonging properly. Sometimes, if you and your friend presented an exceptionally persuasive case, you might be able to manage to wheedle a sleepover out of the day. (Perhaps it was a Friday night and the parents had already begun on the wine.) But still it wasn’t the same.

No, whether it was sooner or later, you went home. This could not be infinitely put off. You hopped in their father’s car maybe and he graciously gave you a lift home. Maybe the family all waved from the car window once they had dropped you back. You left—and they returned to the busy vivacity of their home; the muddle and colourful chaos of their daily life continued on undisrupted, just as though you had never been there. You left no trace in your departure. Or rather, none except the little plate with buttery toast crusts, neatly stacked on the kitchen-counter, or the glass you’d drunk from which had not yet been washed up, orange juice scum settled round the rim. Or maybe the last testament that you had ever been there was to be found in the detritus of toys left sundered on the bedroom carpet, needing to be tidied away. Or perhaps the hand-towel which you had incorrectly folded in the bathroom. You see, other families have their particular ways of doing things, and even the most assiduous efforts to imitate are not always wholly successful.

Between siblings, their play-fights on the staircase recommenced. One belligerent sibling was bound to do something antagonistic such as eat the last of a snack that the other had saved specially for later, filched in one stealthy heist. All these japes, these hijinks, continued when you went home; their world undisturbed. You were just the visitor, after all. A fleeting diplomatic presence on the battle-field, then hurriedly ushered away, sent back to your homeland on the next outbound flight.

After my very first sleepover at nine years old, I cried when I came home at the end of it. I hadn’t meant to cry, for I loved my mother very much and was glad to be back home with her and looked after by her—even if she did tug when she brushed out my long hair. But then again, little girls really do have such ridiculously tender heads—don’t take this for sound parenting advice, but I would wager that it’s probably advisable to toughen them up a little; character-building. Nevertheless, I missed that sleepover so much, the less than twenty-four hours I’d spent at a friend’s house. The euphoria of desserts eaten trussed up in bed, the gleeful tumbling round the house, the late evening hours sleepily telling secrets, and the morning after spent crowding round the family’s computer. Those kind, kind parents—they surrendered the computer to us children without protestation. And we gave our thanks by secretly watching music videos with the expletives left in, bug-eyed with disbelief at our own naughtiness and audacity. We were, in truth, very good girls.

Although I was a fairly common fixture round some of my friends’ houses, nobody ever came round to my house. I didn’t repay the favour.

Because it is not necessarily only unloved children who don’t have the right kind of home to bring others back to. Not just the children with some terribly shameful home-life to hide.

It’s children with parents working multiple jobs or working 7 days a week. It’s children with complicated parents, lost parents, with sad parents or ashamed parents. Children with family problems which are nobody’s fault, not really, but problems which are nonetheless difficult to explain. Children with dirty homes or broken homes—and I do mean literally broken homes: buildings with no bannisters on the stairs, or black mould on the walls, ceilings liable to capsize. The neighbours grew cannabis or were alcoholics. Or there wasn’t enough food in the cupboards to feed the existing children, let alone somebody else’s dear brood. The logistics—the infrastructure, let’s say—for entertaining other people’s children simply weren’t in place in these houses.

Whose houses were your favourite to visit? Did you secretly wish for invitations to your friend’s house who had a trampoline or an Xbox or bunk beds? Something covetable. (As an aside: did anyone else find bunk-beds wildly exciting as a child?) Or maybe there were other valuable assets somebody else’s house could offer you. I refer you to my above point: perhaps there was a cool elder sibling you admired and followed about doggedly. They egged you on in your adoration, recruiting you as a thoughtless little minion, set to work at their disposal, without a single whim or need of your own.

As a child, I loved media which simulated real life. I was always so fastidious about making up games and playing pretend as a child; I took it oh so seriously—retrospectively I can’t have been much fun. So many rules, a baby authoritarian in frilled socks and pigtails! If you wanted to play a game with me then you had to come up with a plausible profile for your character. Your character simply had to have a proper name and not something which sounded made up. You absolutely had to properly situate your character within our fictional universe. Give them a fleshed-out backstory. I wanted what E. M. Forster described as round characters and not flat characters; round characters being those literary creations who mystifyingly (because they sprung from the hands of a crafty author) contain the “incalculability of life.”1 They feel like people you might plausibly encounter in the real world.

It is said (by the faceless voices to whom all great sayings are attributable) that it takes a village to raise a child.

And it really does. Every one of my friends’ houses whom I regularly went to gave me a feeling of security and normality, even if I knew I was only the guest, and this wasn’t really my home. No matter. Some parents manage to parent many more children than those who are lawfully their own. They step in wordlessly and apply themselves to work, knowing there is room in their nest for a couple of other chicks to shelter from the squall outside. Another space at the table—for you. There’s enough to go round.

In the Western world, we are impoverished of community. One of the last and most dependable forms of community we have left is the community which comes from parents, especially mothers. I’m not going to discuss movements like pronatalism, though I suppose you might construe this piece as adjacent to the discourse, certainly if you wanted to be a bit contrary anyhow.

These communities are formed suddenly and out of necessity. Let’s paint a roughish picture. Heavily pregnant, you find yourself at a baby-group, learning how to correctly cycle your breath and fight off panic attacks at birth from a New Ager doula with dubious healthcare accreditations. The doula enjoys aphrodisiacal incense and forces you all to listen to mournful recordings of whales singing, and would definitely be found guilty of cultural appropriation if prosecuted by a liberal jury. The other women in the room may all be of different backgrounds and ages and demographics—you may have nothing in paper on common, other than that you are both about to step into that lofty vocation of maternity. In fact, maybe in other circumstances, you would actually take a disliking to some of these women. Drinks lobbed at parties, favourite going-out tops soiled with red wine pigment. Choruses of shrill insults and catty back-chatting, truly bottomless bottomless brunch sessions spent dissecting why she’s such a cow and so forth. But yet you find solace in their mum-friends (tell me, why does this sound pejorative, somehow?) in ways that you feel marooned from your single or childless friends.

Being on the precipice of parenthood, or fighting tooth-and-nail through the terrible twos, perhaps living far from your own family, having moved away—all of this invites community-building. Necessity is the mother of invention. And motherhood is often, in turn, surrogate to necessity.

Going round to other people’s houses filled a hole in me as a child. It finished the job of parenting that is best done by community. Even a relatively loose community which requires very pro-active parents to ensure its upkeep, and necessitates rather a lot of car-pooling given we all live so far from each other these days—where once upon a time, maybe in our parents’ generation, people were friends with their neighbours and freely sent their children trotting off round to other people’s houses at a moment’s notice.

It strikes me that a Part 2 of this piece might be a disquisition on university halls, and living in such close proximity to your closest friends, en masse—or at the very least people your own age. Or you are so frightfully bored that I think better of this and politely desist.

Thank you for reading—and a happy new year!

Forster, E. M., originally in his series of lectures Aspects of the Novel (1927), but I cheated and got this from the following website: https://www.supersummary.com/round-character/ Given I am not usually so lazy with my background reading, I am going to ask that you let me off just this once.

so in love with this. Brought back so many childhood memories of the friends who’s homes became my second home and families became mine too

this piece is v special to me!