A small amount of curiosity is better than nothing.

You might not be as inquiring as the ancients. Those who lived for the hot romantic pursuit of dialectic crescendo: the climaxing little deaths of ignorance to knowledge. And you might feel no desire to stand immobilised for hours, fussing over an inert little potted sapling, and making many fibrous cuttings with a rusted pair of secateurs, transplanting the botanical analysand into a propagating glass. A pretender to scientific thought. There’s a homunculus contorting itself into an arabesque beneath a glass cloche or crassly picking its miniature nose, for total want of stimulation, since it is an experiment you have subsequently lost interest in. No, you might not be quite this curious.

But to have zero curiosity is to live entirely complacently. It is a condition of total vacuity: a dusty planetoid without any population, no flora nor fauna, nor any seasons, nor any weather; just air and rock and empyrean emptiness.

I don’t really mind even if the small amount of curiosity you do have is extremely tame. Tamer than a glassy-eyed bird basted with opiates, too risk-averse to hop out of its gilt cage.

But there ought to be some curiosity, all the same.

Even if it prefers to abide by either-or distinctions, or to choose between two poles, or superintends a propensity towards pre-determined conclusions. A slavish love of the label.

Now. Let me ask you this. Would you rather be asked the uninspired question ‘What’s your MBTI type?’ or ‘What’s your star-sign?’ or even ‘Are you a dog or cat person?’ or not to be asked anything, ever, at all?

It might be preferable, granted, if people were more comfortable with accepting complexity as a given. If we had moved beyond the compulsion to box ourselves in, and use simplifying or caricaturising labels to describe ourselves, to make ourselves more immediately knowable. More able to be situated socially, more slinkily and snugly occupying a recognisable territory, a homeland of personhood. A reference point. This new person I am just now meeting for the first time tells me they’re a ‘diesel-head’ which suggests to me certain connotations, based upon the availability of previous impressions and encounters I have to draw upon—ie. my dad’s best mate Rob loves cars too, therefore I can deduce with some probability that this new person might be a bit like Rob.

But, equally, the onus also falls on us to approach the labels other people use about themselves with critical thought. We have our own responsibility when meeting other people to recognise that a label, however well-chosen or cleverly named, does not tell us the full story.

If someone were to tell you that they think of themselves as a football fan, then we should be able to offer them the grace of believing this identity to suggest a greater, more epic story than just ‘I support Chelsea F.C.’ Possibly this straightforward-seeming identity is a useful shorthand which sits squarely over the top of many layers of depth. Maybe attending football games represented the only one-on-one quality time this person was able to spend with their blue-collar father, whose punishing job sucked up all his time for a pittance of pay. Whilst we might scoff at labels, and demand with impunity what exactly does it mean to be a ‘Swiftie’ or a Christian or to be a loyal follower of the Premier League? what does it tell me about you, personally?—we might also be missing part of the point. Which is to say that whilst we might consider labels to be shallow, the label itself is also only really a pit-stop or a sign-post, which can (if we are willing and curious people) usher us onto a more granular tale.

But then—the obverse can be true, too. For we know all too well that, in chastening contrast to the wholesale fullness of real experience, labels can have frustratingly constricting qualities. A label might purport to mean X, but you are using X label in a postmodern or an ironic way, or maybe you’re only using X label as a make-do or a stand-in, because there isn’t another descriptor which comes anywhere close to representing you. ‘That’ll do.’ ‘That’ll suffice.’ Labels can assume the strangulating warfare of a military bottle-neck, where out of a crowd of thousands of men only a drip-feed of soldiers can flee the battlefield.

I knew a psychologist who wasn’t keen on issuing diagnoses to her patients because she believed diagnoses all too readily mutated into self-fulfilling prophecies. She upheld that it was more helpful to treat a patient’s symptoms and thought-patterns, the things actually impeding upon their day-to-day existence, rather than getting bogged down in whether or not they suffered from XYZ pathology or not—or, battling semantics, whether perhaps they suffered from a sub-clinical variant, or appreciably displayed signs of XYZ—just rather atypically. Of course, this argument could be challenged quite simply: it can be helpful to give a name to a pathology, to know what we are dealing with, and to decide what sort of treatment might be most effective.

Names, even as they risk proving reductive or mangling the intricacies of individual experience (it’d be foolish to believe two people with depression lived the same life), assist in the pooling and transfer of knowledge between parties. Two researchers can work in tandem, despite being located on opposite ends of the globe, towards a cancer cure, if they both know the name and nature of the beast they seek to slay.

On the one hand, (perhaps cloyingly optimistically) I believe that we as humans are able to comfortably—and productively—exist without a reliance on labels. If I meet you, I shall aim to take the time to get to know you. In this process, you are not required to abridge yourself, or to dissect yourself into nameable units to expedite the process of my doing so. Like a good journalist, I shall strive to learn you inside-out through thoughtful questioning, faithfully recording your answers, and supplementing my study with a good deal of research. I’ll speak to your friends about you. I’ll respectfully observe how you carry yourself.

But, nevertheless, we do use labels all the same.

Let’s use a relatively well-known identity test as an example. The Political Compass. This test nobly seeks to plot you and your politics on a grid between the axes of, essentially, FASCIST AUTOCRAT and MARXIST SUPREMO DICTATOR. (It is always good to have one’s bearings with us and to know where we are, I suppose.)

Imagine you chug through the test, gamely responding to each proposition, and, naturally, you expect in return to be propitiated by learning something about yourself. We are all lovers of flattery, and our very own selves are typically our very favourite topics; therefore a novel interpretation of YOU stands a chance at being something you are very much interested in.

Obediently you tell the website what you think. Input all your opinions, finish the test, and wait to ransack the data.

But, imagine, this time the website didn’t generate an answer. It didn’t reveal to you nice little named identity. (Even if the name would only have been what you expected—the recognition that maybe you’re a vaguely left-of-centre political agent unlikely to cause any insurgency or agitation, less likely still to ever hold office, and probably most inclined to vote as you have always done, possibly paying more heed to proposed tax breaks than to pureblood political theory).

Anyway, the test didn’t give you anything. It didn’t give you the heraldry of a Confirmed Identity. Imagine it simply regurgitated your answers back at you without telling you what they meant. If you said you agreed with Point X, this opinion didn’t make you a centrist or a socialist, it simply meant you agreed with Point X. You feel cheated!

For you were not ascribed a label or an identity. The transaction—your opinions in return for a prophetic parsing of what these opinions said about you—was apparently redundant, sulkily moot.

You were simply forced to exist with your opinions and that be the end of it, without those opinions contributing to some nameable whole. You’d perhaps hoped that these opinions of yours might, when lowered into the crucible of analysis and extracting meaning, birth you a new, recognised identity. This identity you could then equip like a well-tailored coat on a gloomy day, and bring with you wherever you go, for this identity might helpfully possess some social cachet for you to use in your everyday life. This identity could give you a new and (again) nameable way of relating to your peers. ‘Why are you three friends?’ someone asks a trio of twenty-something men in quarter-zip fleeces at a bar in central London on a Friday night. Pleased to indulge the part-castrated eros of revealing something (anything) about themselves, the trio chirp back in unison: ‘Oh, we’re all Liberal Democrats!’

On the contrary though, I do think labels can be exciting conduits to new knowledge, new points of view, and new avenues of thought. They’re not perfect and neither is the transit which they offer. They’re like the Venetian men who row gondolas up and down the canals. Labels. You pay them a bit of money, shiny euros clinked into hands more golden than vintage leather, and shakily jump into their rickety vessel—even though you know it’s possibly not watertight and you stand to ruin your shoes. Not quite comfortably seated, you allow the terse Italian to glide slowly on towards your destination.

This is a bit of a digression, but we won’t spend much time with it—you have my word. Recently I’ve been reading the writing of The School of Life or Alain de Botton, which is basically a rehash of Freudian psychoanalysis. I don’t know that I entirely agree with the points they make, but I read this writing secretively (and circumspectly!) in the same way a highly-educated and successful woman might devour inane and trashy rom-coms. I just like it. Perhaps subconsciously I imagine it might make me a better lover, maybe I just gravitate towards writing which thematises love, maybe I’m using these conspicuously male-authored writings on love as a substitute boyfriend—I don’t know. Theorise away—that’s the chief appeal of psychoanalysis anyway.

Defensibly, you could say that within psychoanalytical explanations of human behaviour (especially when examining romantic relationships as the subject) there is an over-emphasis of ‘childhood trauma’ and its incidence. Enter all the typical indictments against modern psychological language and its adjuncts. We’ve lost, weakened, and attenuated the meaning of clinical descriptors like trauma; suddenly everyone is traumatised! Mediocre (not abysmal, not fabulous) parenting of a child suddenly guarantees that said child’s future relationships will be doomed—it predestines their divorce once grown up. No soul emerges from psychoanalytical scrutiny without being judged irremediably broken. You stand up from the sagging Freudian sofa rendered a shadow of a man.

And yet, whilst I believe that love is absurdly complex (to say the least!), I found a naughty sort of empowerment in some of the labels being dangled before me. I grew curious about attachment styles. Probably you have heard of these; it saves me as the writer a lot of trouble if you have. If you haven’t though, your homework is to look them up and also to take a quiz to find out your own.

Mistakenly, I initially thought I had an anxious attachment. Probably because I relate to the umbrella term anxious in so many other aspects of my life. But recently I realised that, consistently, across many many relationships (familial; platonic; even institutional) I was terribly avoidant. It was laughable how I’d missed how well I fitted the—agreeably latitudinous, so as to be a catch-all and prove applicable to many—description.

This embryonic epiphany gave me a real kick. Why? For I associated avoidance with being a masculine style of loving, and I lionise—I love—the masculine. I wish I understood it. I wish I had it.

Thus the rather banal (and, depending on who you ask, meaningless) label avoidant to me signalled an estimable degree of success. It meant I was doing something right. Labels can, as we have discussed, operate as a degradation of individuality. They can negligently attempt to homogenise the specific into the group, even if only one or two traits are shared in common. And yet for me, this label which could reasonably be applied to maybe half of the population, was a kind of uplift, or exaltation. It was a corridor towards further meaning. Conveyance. Gladly I entered into it—and hastily shut the door, scrabbling at the locks, so as to prevent any other girls from slyly taking the initiative, and following in my foot-steps, latching onto the precious special-ness of avoidance. Catch me if you can.

But then another part of me pipes up inside my brain—like the first time a quiet clever child raises their hand in class. What does knowing this word and using it actually offer you? Why is it valuable? Well, I’ve just told you. It’s valuable because of its connotation. To me, avoidance means masculinity, and masculinity is better than that which I am and have, the weak-natured over-loving femininity I’ve always had, and sometimes loved, and sometimes begged to be able to run away from.

Therefore I liked the label of avoidant because it seemed to be a precursor to another label—masculine—which conferred some status unto me, and might makes others treat me differently. These days I like to surprise people. Once, I loved being the Alice I once was, who everyone thought of as ditsy, the girl who cried in the library over poems and wore dresses exclusively, and would have kissed the ground her prince walked on.

But nowadays I find myself at war with that past Alice.

Let’s be literary; let’s be allusive. Do let’s. I have become like Britomart in The Faerie Queene (Edmund Spenser; 1595), who thinks that putting on a suit of armour and taking up a sword erases (pleasingly!) her femininity all the way. It makes quite the man of her.

She tries so hard to be masculine. And, with all due respect, she had a good run for a while—cantering about through the wilderness, picking duels with knights and winning them. But still she failed.

What happens? She falls in love with a man, and finds herself quite the woman again, tearful and lovesick and deliriously, maddeningly feminine in her bedroom. Her nurse comes to attend her—to give her a good talking-to and suss out what’s going on. Britomart moans that her ‘stubborne smart’ is ‘no vsuall fire’ but rather some perplexing ‘melancholy’ ‘which on my life doth feed, / And suckes the bloud, which from my hart doth bleed.’ The nurse seems to laugh—to ask is that it, is that all? ‘[W]hy make ye such Monster of your mind’? The nurse asks. It is only love! (Book III, Canto II, mixed stanzas.)

But to Britomart, she has been emasculated entirely—even if she had nothing netherward to castrate in the first place. It is awful for her to be placed in the position of lover.

But, I think it can be said, that Britomart learns to reconcile two impulses. On the one hand, there is her abstracted vision of masculine independence, and her conception of what it might be to be a man—summatively, the ability to exist without others and certainly without love. On the other hand, there is the bracing newfoundland of the feminine positionality of lover, who seeks to be taken care of, wanted; who is distinctly dependent. She recovers from the painful symptoms of her lovesickness—yet manages to do so without having to banish love from her heart. There is a solemnly moving scene of her rising from her sick-bed, and putting on her armour once more, to mount another quest for the first time in a long while. But not as before.

She learns to recognise that, in the other male knights she meets in her playful skirmishes, they do not deal with their feelings as kindly or as appropriately as they might. ‘Ah gentle knight,’ she purrs comfortingly, when ministering ‘[f]it medicine’ and ‘reliefe’ to a suffering man. She tells him, partly in admiration and partly in admonition, that his ‘deepe conceiued griefe / Well seems t’exceede the power of patience’. (Book III, Canto XI, stanza 14) He has borne his inward pain alone and unassisted far too long.

…Perhaps, I muse, some men still identify with the image of knight? Or of soldier—what you will. Same thing; both supplicating before a central ideal of heroism.

This essay was originally about labels, wasn’t it?

To conclude, a few peace-making words.

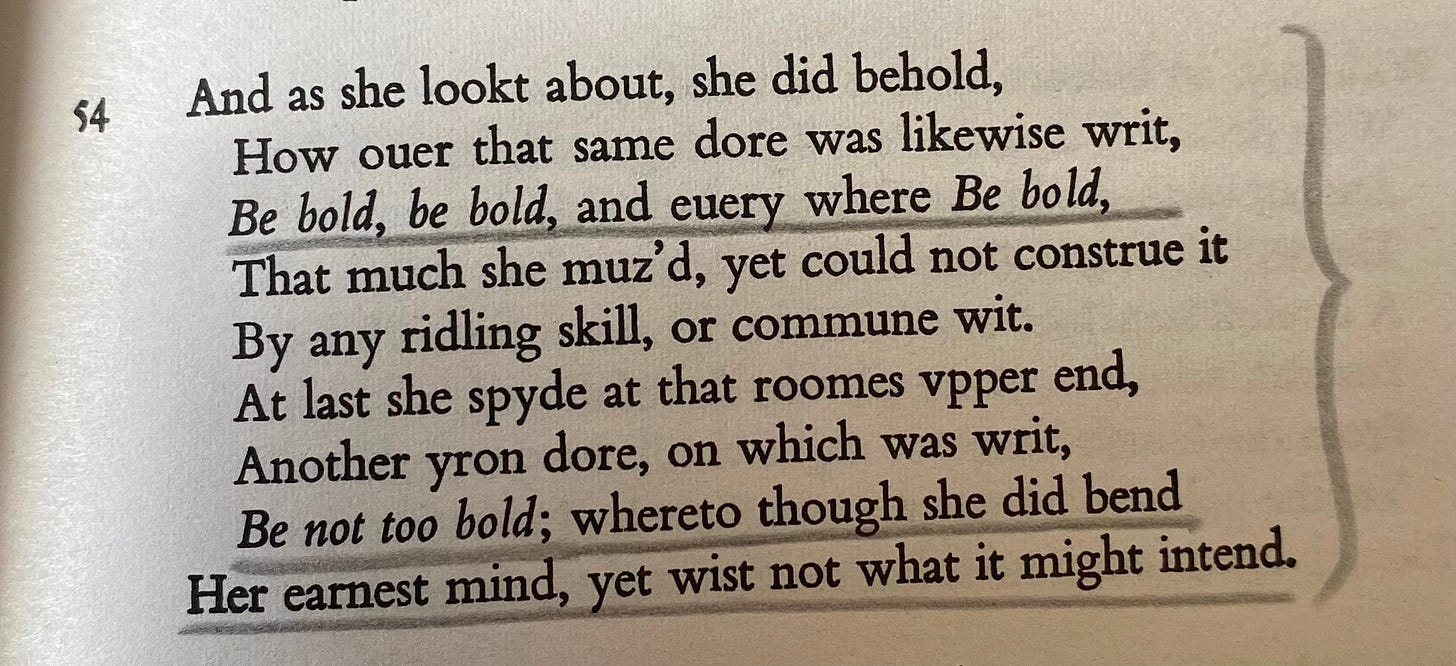

BE BOLD, BE BOLD … BE NOT TOO BOLD.

This passage seems to sum up how Britomart comes to balance masculinity and femininity. Be bold, but not too bold. Find a limit. Learn to surrender, but be sure to know how to fight tooth-and-nail for what you want as well. Do not be anyone’s victim. But, should you be so blessed as to find love, whilst not giving yourself over to it immediately—perhaps there is a way to let it in, to (oddly) befriend it.

Look, there’s some good in labels. I know of, and perhaps you do too, people who found safety and belonging in labels. Especially when it came to understanding something like their sexuality. It’s not my place to write on something so significant to so many, only to pay sincere deference to this.

I also know that some labels may delineate the single most important thing about a person’s life—especially when the label chosen denotes someone’s religion.

They can be exciting—labels—and they can be transitional. Aides to something new. They can signify new experiments we embark upon with our presentations, personalities, and perspectives.

But I wouldn’t like to see someone conform perfectly to a label. A label which, while expedient and intelligible to a great many people, can only be used at the expense of the user’s own birthright of complexity. Again, this is with the exception of things like religion, which in many ways is about the total surrender of worldly identity to a greater salvational cause.

Thank you for reading!

Cover image—Pigeons by Henry Voordecker (1779 - 1861)

this is a wonderful text, so much to dwell upon and interrogate within oneself 🤍

very interesting. I'd not heard of attachment styles. A quiz tells me that I'm avoidant. The labels don't leave much doubt about what's best: who would want to be disorganized or anxious when they could be secure? (It brings to my mind a review by Brian Barry of Steven Lukes's book on power. 'The conceptual core of this essay', Barry writes, 'is the contrast between three views of power, which are called the one-dimensional, the two-dimensional, and the three-dimensional view. (The terms, it need hardly be said, are not neutral. Who would willingly accept a one-dimensional or two- dimensional view of something if a three-dimensional view were also available?)')

I wonder whether these quizzes push people into the attachment styles other than secure (just as, as you note, perhaps psychoanalysts over-diagnose childhood trauma). For why pay for anything the websites might sell if you've got it made already? In that way they would be functioning in the opposite direction to how the Political Compass (as Oliver notes) does, being biased away from the option conceived of as good.