Comfort, Platitudes, and Love

I rather like being told nice things, don't you? Also this gets very medieval; I'm incredibly apologetic.

Semi-seriously, I have been looking at joining a convent recently.

I know I wouldn’t actually join one but that is almost beside the point. My mother’s greatest fear as a teenager was experiencing a calling, namely a vocation of some sort (usually delivered by a dream or a seraph who enters your dream).

A vocation is inescapable. You can try to fight against it, but if you are meant to be a nun or a monk, you will eventually have to surrender to the calling. Otherwise it will follow you peripatetically and you will not be able to rest.

Anyway, my mother was actually taught by nuns—real, live nuns—at the school she went to, since demolished, in East London in the 1970s. Many of the nuns’ sayings and aperçus are mainstays in our house. One of the nuns who taught my mother cooking was named Sister Philomena, and it could be said that Sister Philomena was slightly melodramatic. Although I never met this formidable woman myself, I feel I know her well. Whenever I cook and am not duly diligent in tidying up after myself—all the detritus of onion skins and carrot tops collecting in dung-heaps by the chopping board, my mother lapses into a rendition of Sister Philomena. She adopts a thick Irish brogue and exclaims in pained dramatic tones (it’s all very unnecessarily baroque): ‘I had a dream, in fact it was a nightmare, that Alice State did not clean up after herself as she went along’. This wry derogation is always enough to spur me into action; transforming me from lax modern girl without any instinct nor aptitude for housewifery into an eager-to-please Victorian scullery maid.

Truthfully, I think I would always have come to the conclusion of religion myself. I always and predictably seem to bump into Catholicism. Sometimes it is deposited on my doorstep like a bunch of flowers from a particularly dogged admirer. I will pay attention, whether I like it or not. I cannot escape it. The Church is the eager bride-groom and you the bright-eyed bride; courted, won over, tamed. My best friend Aliyah told me when we were seventeen that I’d be a great English teacher at a Catholic school (unsure if this constitutes a character assassination or a compliment). My dear friend Grace told me two weeks ago after losing my job that I should go on sabbatical to a convent in Italy. My mother looks at me doubtfully as I try to devise the best way of punishing myself for all my major mess-ups—how to maximise one’s punitive bang for one’s buck—and says, sighingly: ‘Alice, I worry you have inherited some terrible Catholic guilt from me.’

Catholic guilt. Is it so terrible? We cannot live well and honestly without some method of self-examination. Pick your poison, I suppose. We are often such castigatory creatures, whether it is religion which impels us to be so or not. The same page of a young girl’s journal can teem with lines of gratitude, describing devotion to beloved best friends, whilst also containing a concerning slew of of self-hatred, atomising her own body into a series of issues or hang-ups which must be addressed. Similarly, as western society has furthered itself from the scaffolds and strictures of religion, our modes and chosen oeuvres of writing have become more and more confessional in nature.

Poetry seems to always spotlight the ‘I’ nowadays. We don’t write dramatic monologues about other people—we don’t use poetry to tell stories anymore, like our Romantic forebears did, for instance. Rather poetry has become for us a more ostentatious iteration of a diary entry, in which we detail our thoughts and feelings, gesture to some faceless lover, then end up in an intestinal pit of self-absorption.

And thus it comes to be that my laptop’s search history is now chequered with various convents. Get thee to a nunnery indeed.

One of these convents advised all aspiring neophytes, however, to ensure all their finances were in order before joining. I suppose I would not be the first person trying to escape monetary worries through the protectorate of the cloister. For many of them seem to operate in a world wherein money does not exist—or rather it exists as a kind of secular token—malapropic—something which although acknowledged does not signify anything to them. From what I can tell, in many convents rooms for visitors are often free, or lodgers may barter their skills and time—in gardening, cooking, or building, perhaps—in exchange for their board.

So much for the convent plans. It is not looking as though I will be a nun anytime soon. But what I was looking for, as I trawled the Internet for convents to materialise at, was refuge. Comfort. Serenity. Safety. These good, pure, human things.

It makes sense biologically for humans to be comfort-seeking creatures. Even as we grow old and lay claims to greater personal independence. Look at cats, for example. They can seem so indifferent to us for the majority of the time. As though they do not need us. Maybe they even hunt their own food, turning up their nose at the unappetising, pre-packaged mulch we serve them. But then, have you ever seen the way they snuffle into their owners? Burrowing their heads into your chest, swatting at your face with a paw, their wide and curious eyes begging solicitously for our attention. As though they were kittens again, milk-scented and weak. Half an hour later, I can almost guarantee you that the cat will be pretending this never happened—it’ll give you the cold shoulder and act as though you did not exist, snubbing you entirely.

This year, to try and seek comfort, I tried to read more. Not a particularly original scheme, but a tried-and-tested one. Because surely that is one of the tenets of good comfort-seeking—you incline towards the familiar; you do what others have done before? Anyway, at any rate I read many pieces of writing—of variable quality—on love and heartbreak. Really, if I had been sensible, I ought to have jotted down the quotes which affected me most, the quotes which I derived the most comfort from, but in the moment it usually slipped my mind to do so. It would have been nice if I had emerged from my programme of reading with a notebook—a common-place book—stuffed with comforting quotations on heartbreak, pretty lines I’d copied out and inscribed.

Scrapped plans. This essay was also going to be a piece of dogma. How should we love? Why should we write? Where should we find and source our comfort? This writing was to be sermonising and fierce. Claws unsheathed and the vocabulary accusatory and uncompromising. Visions of wrath. My writer-woman’s body would play host to Martin Luther or the spectral visitant of some other such religious figure. White-knuckled, I’d grip his quill pen from where I sit, five centuries after him, writing at my dining table. Yes, Luther or some lesser-known sanctified bygone would write through me furiously, scratching ink through the parchment and lacerating the surface of the desk; spewing out a concordat exhorting everything he knew and felt to be true about divine love and the ways man ought respond to it.

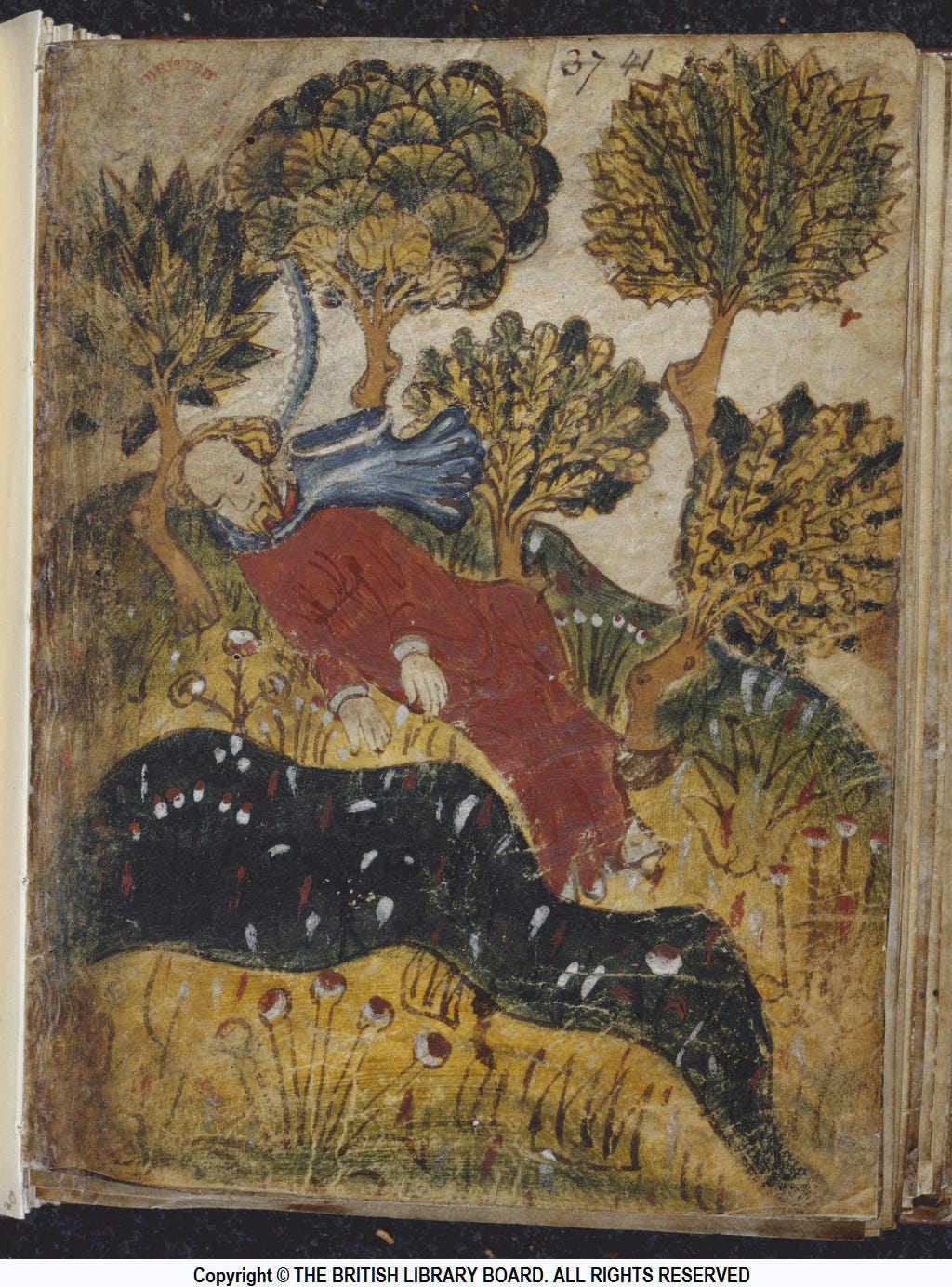

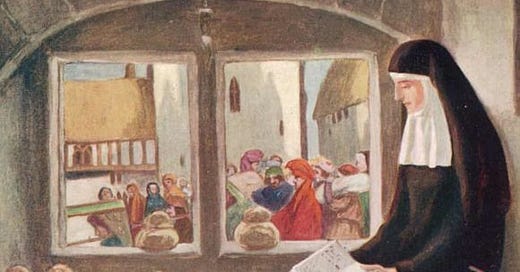

Or maybe I’d have spurned Luther and instead impishly played pretend at being a Christine de Pizan or an impostured Hildegard von Bingen. Let me detail this emerging medieval tableau with inks and viscous tempera pigments. All smocks and hanging driftwood crucifixes and handsewn scapulars and streaming curls neatly tucked away beneath white linen wimples (fig 1.). Hermitages and anchorites’ nests (fig. 2); silence and billowing incense-smoke; yet more quills—aviaries’ worth, sparrow-tails and hawk-wings, more sheafs of parchment paper, more genius bleeding out onto the pages.

In a few nimble bounds, I was going to scramble up to the pulpit, adjust my collar, smooth down my papers, tap affirmatively on the globular little microphone, and say something hopefully crowd-pleasing to my waiting flock of lost sheep in the pews below. Between the heartfelt pleas of my words and my sincere oracy—my bids to make lasting and connecting eye-contact with a few certain members of the congregation and lift them into agreement with me, I would win you over to my theodicy on love.

And then I paused and wondered: why the great effort? Why the persuasion? Why should I tell you how I love? Why should I expect you to dwell upon it, think me either stupid and lacking in selfhood or perhaps a half-blood angel.

What are so many of us writing if not our own manifestoes on love?

Forceful treatises. Hot breath whispering advice into ears, pouring it out, dispensing it whether wanted or not. This is that which I believe in, that which I live and die for and by.

As a romantic and a reader, I scan through my favourite novels and poems for evidence of other people loving like I do, or did. Pick-axes and sickles are applied to book-pages and an effortful chiselling begins, in order to try and excavate the perfect quotation which sums me up. I glare angrily at the likes of the old masters and dare them to one-up me in the game of love.

What’ve you got for me, Byron? Womaniser. (I hiss this under my breath.) Then I check on the other Romantics to see if they have anything better for me to choose from. Par for the course, and just as we all expected, Percy Bysshe Shelley is too busy writing rousing poetry about class-conflict—about the Peterloo Massacre (1819) in a fit of proto-socialist disgust. Or, perhaps, writing his wife’s novel Frankenstein, if you don’t believe that Mary Shelley wrote it herself. Samuel Taylor Coleridge is too busy inventing literary criticism to bother much writing his own poetry anymore; he said all he wanted to say and it was mostly about albatrosses.

At length I begin to despair of the Romantics. Nominative determinism sold me a lie: their name had suggested they might have better things to say on the theme of love.

But then—aha. Chaptered at the end of an anthology of Romantic verse, I stumble upon a subject likely to deliver what I want. Here he is. The lovelorn John Keats is found in his native territory, crying pathetically into his letters and speaking to us—ironically by himself quoting Shakespeare to aid the articulation of his pain:

‘Shakespeare always sums up matters in the most sovereign matter. Hamlet’s heart was full of such Misery as mine is when he said to Ophelia “Go to a Nunnery, go, go!” Indeed I should like to give up the matter at once—I should like to die.’ — ‘I hate men, and women more.’1 (Letter to Fanny Brawne, dated August 1820.)

But where should we find comfort?

What you could do right now, I suppose, is search idly online for something like ‘William Shakespeare quotations on love’ or ‘Jane Austen quotes on love’ or ‘what did Saint Augustine say about love’ and see what results you retrieve. Probably you will be directed to a Goodreads page, patchworked with a miscellany of botched quotations, or more injuriously, perhaps one of those educational literature websites aimed at coasting high schoolers. Someone else has already done the leg-work in compiling what the old masters have previously said on love, their old and well-worn sophistries.

But don’t. These quotes which you can forage for online are doubtless lovely. Beautiful cut-and-pasted couplets. But fundamentally, even when we parse transcendent and enduring truths from these old sayings, they will not necessarily be what you need right now. They’re not necessarily medicinal to you, the sage doctor mightn’t prescribe them. But then again, obviously reading is one of the finest methods we have for channelling empathy. It is a brilliant way of realising that you are not alone. Famously, James Baldwin said in an interview in 1963: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.”2 Do read, of course, but what I really think will supply you with comfort is if you write.

Stop ventriloquising your hurt through other people’s voices, as if it made your hurt any worthier. Why, beyond an immediate desperate search for comfort, do you need to look for someone else to have said something moving about your circumstances? Say it yourself! You’ll probably do it better than anyone else could, too. What’s that oft-given writer’s advice? Write the kind of thing that you would like to read yourself.

When we are hoping to find comfort, even when we turn to literature, to force it to say the things which we are unsure how to—it must be intentional. Could it be true that you derive more comfort and strength a text message from your best friend, over a line of Shakespeare? Even if said best friend only recycled an existing cliché, and delivered said cliché through a multitude of bitty, typo-ridden messages, over perfect iambic lines rolling off the tongue—maybe that feels more moving to you?

I could quote Keats at you. Indeed, I already did—but crucially this was only because I thought it was relevant to what I had to say. His words productively scaffolded my own argument. For Keats said something with more succinctness, style, and even boyish petulance that I could not have said quite so aptly. I put myself out of my own writerly misery by letting him sub in to the game momentarily, if you will—a half-time changeover whilst I scampered away to sit on the bleachers, kicked off my trainers and downed a fluorescent bottle of energy drink with great relief.

It is probably just a hang-over of spending too much of my time in the past three years reading and writing useless essays for a useless degree. I call it citation anxiety, or bibliography insecurity. This encapsulates the displeasing feeling that I do not have enough footnotes in my writing or that I should be quoting more people—that if I were cleverer I would be quoting more people—the correct sort of people, too, the intelligentsia—ideally recruiting as many of their opinions and findings into my writing as possible. Paragraphs thicketed with other people’s writing and other people’s opinions gummed in; the work of a slipshod bricklayer trying their best to erect a house as quickly as possible, gluing together long quotations with an unforgiving slurry to give an impression of cohesion, wholeness, cogency to one’s writing. It just makes it all look better—having people at hand to quote. It’s the essential premise of name-dropping when in conversation or interview. Makes you look good. Where are the prefabs of essays, the cookie-cutter Levittowns?

I find that even at my big age I’m often looking to be coddled and soothed, a little like a colicky baby, whining and wakeful through the night. Sleepless parents with bluish under-eyes, imploring the child to sleep. Doing anything they can to promote its comfort. Driving it round the block over and over; hoarsely whispering lullabies—soft but tuneless canticles; warming milk to the just-right temperature, following old Goldilocksian scientific theory.

There are so many methods we can use to try to comfort ourselves. Many lack much backing, fewer still any credentials. I saw a post on Instagram before I dramatically absconded from the app which read something like: ‘When it’s midnight and you wonder if you actually want that sandwich or whether really you want to be loved?’ (All my friends with eating disorders had liked that post. In a similarly cavalier spirit I think I liked it too.) Yeah, food works as a sticking plaster; it helps in the short-term—I’ve got no real words of wisdom for you on this here. There is a whole essay in this, an essay which I want to write, but am not writing now. Anyway—there are fine lines between so-called self-care, self-love and self-harm; very fine lines—like the first whisper of maternity surfacing on a pregnancy test, that near-invisible little marking.

I find comfort in the fact that we have always needed comfort. We have always been such comfort-seeking creatures. Even at points in our history when the dominant culture, at least from where I write in the West, seemed to prize sufferance and pain over relief and ease. What sort of moods and feelings do you associate with the European Middle Ages? Does it feel like a particularly comforting, easy-going time to have lived? What was the average workaday person’s experience of life—did they often go hungry and cold, did they chafe from coarse clothing, were they left with welts or festering, untreated infections? Peter Laslett, in his seminal (if very much of-its-time) work of history The World We Have Lost, reminds us that centuries ago: ‘The simplest operation needed effort; drawing the water from the well, striking steel on flint to catch the tinder alight, cutting goose-feather quills to make a pen, they all took time, trouble and energy.’3 It would be so easily to think of the Middle Ages as an entirely comfortless time. But, on the flip side, if so little in life provided immediate, gratifying comfort—then surely it makes sense for comfort to have been greatly valued? Chased, sought after, woven into the philosophies and value-systems of the age?

Earlier, if you’ve been paying attention (and I of course stifle an insouciant giggle here; I for one wouldn’t blame you if your focus had wandered astray), I mentioned the fourteenth-century anchorite, Julian of Norwich. She wrote a work titled A Revelation of Divine Love (1373), which was purported to have been written out for her by an amanuensis to whom she dictated her testimony, being personally illiterate. The text is devotional, brimming over with worshipful love of Jesus Christ. One of the most touching lines in the text is this one: ‘[Jesus'] will wee be solacid and myrthid with him till whan we come to fullhede in heavyn’. If you are unfamiliar with Middle English, I have glossed this as saying: ‘Jesus wants us to be happy even until we come to our full potential, when we are reunited with Him in Heaven.’ Jesus, apparently, even wants us to be ‘myrthid’. Jesus wants us to laugh, Julian says—suggesting that that beautiful feeling of joy is holy. Laughter, the abulous levity of life, is sanctified.

Julian’s God does not blame mankind when we lapse. Julian’s God is not interested in showing any ‘manner of blame to me ne to non that shall be safe’, but rather is interested in forgiveness, and in loving His followers ‘full tenderly’. There are many parts of herself with which Julian is displeased. There are facets of her character in which she feels she comes up short. ‘If I loke singularly to myselfe,’ she says, embarking on a mission of self-scrutiny, she finds that she is ‘right nowte’—ie. nothing, worth nothing—but then she adds: ‘but in general I am in hope’. Even though she is so acutely aware of all her manifold shortcomings, Julian believes that God ‘made all things for love’—including her, sinful her. Julian goes on to compare God to a mother, inflecting her writing with a cadence which feels almost—forgive me—rather in-keeping with the style of modern (girlboss?) feminism we have seen for the past decade or so.

Let’s go back even further in time. Stay with me now. Dark, dingey cellars. Squat tallow candles, sputtering wax, a flame engirdling a wiry blackened wick with a halo, light like a gold plate. Silver-haired cobwebs overhead. Stained glass windows in vermillion, emerald, cobalt. As for your clothes, my costumier has you all kitted out: you’re dressed in horse-hair beneath your linens and a cold metal crucifix hangs suspended over your breastbone. You spend your time (I am quite certain you have been taught to read) with your head bent resolutely over your Bible. Yours is a small but not unremarkable copy, about the size of your palm when splayed out, and one of the monks painstakingly copied out the text for you. (He is definitely in love with you but you’re obviously not interested and, like you, he is also meant to be celibate. So, uncertain how to channel his desponding energies, instead he makes beautiful illuminated manuscripts for you instead of kissing you. Poor lad.)

Anyway, I’ve done all this because the text I want to talk about, the Ancrene Wisse, was written at some nebulous point in the early 1200s to serve as an instructional manual to novitiate anchoresses, preparing them for their life in contemplative solitude and religious service. The author addresses their readers as ‘mine leove sustrene’—‘my beloved sisters’. In fact, taken on the whole, you might be surprised how loving the tenor is which is used in this text. It was a text which so easily could have been rather berating, giving out long and stern lists of rules and regulations which the anchoresses had no choice but to follow. Somewhat permissively, the author claims: ‘Euch-an segge ase best bereth hire on heorte verseilunge of sawter’, which I read as meaning: ‘Each [anchoress]’s heart will guide her best with versifying the psalms’, in turn meaning: feel free to translate and take from the psalms what you need. Your own heart will inform you best. You know yourself. You are wise. (I am sorry this has all been so needlessly, tiresomely protracted. Love the medievals, but I am not a medievalist!)

The author even goes so far as to actively encourage the sisters to heed ‘ower anne wise’—to follow ‘your own opinion/judgement/wisdom’.4 There is also a real protective streak from the author; they want to look after these devoted women, these hidden worshippers of Christ. They are told not to force themselves to suffer unnecessarily. ‘Al thet iche habbe i-seid of flesches pinsunge nis nawt for ow,’ the author makes clear in no uncertain terms: ‘all that I have said of fleshly suffering is not for you’. Our author proceeds to acknowledge, sadly, that anchorites usually ‘tholieth mare then ich walde’—they typically suffer more than they need to. They choose to suffer out of their own volition, perhaps mistakenly believing that it strengthens their worship. However, contrastingly, the author also claims that some women are often ‘to softe’ on themselves—even to ruinously give themselves over to temptation and thus become so impossibly evil that they turn into wolves—‘forschuppet into wulvene’—so, you know, you win some and you lose some. Can’t have everything.

This is to say that our very distant ancestors of the medieval past—those who we think of as being so pious and so ascetic and so sinlessly perfect—they also wanted to be comforted. They sought comfort in their religion and in the very fundaments of their religious practice.

One last medieval text—just one more, I promise. This one is Pearl, which is a mysterious poem with an unknown author, written in a distinct dialect of Middle English—a variant tracked down by the valiant enterprises of sedulous literary scholars and philologists to the Midlands. The poem is about a man who carelessly loses his precious pearl (‘þat pryuy perle withouten spot’) in a garden—‘Allas! I leste hyr in on erbere’. He struts around looking for it for awhile, then gives up, lying down in the grasslands. It is important that I now mention that a common reading of this poem is to assume that the lost pearl represents the man’s daughter—who has died. This is a grieving, deeply unhappy man.

He dreams that he meets a gorgeous young woman who embodies the pearl, who has given her life to Christ and worship of Him, much like our friends the anchorites, shuttered away in their bleak cells. She speaks to him, a doe-eyed little creatures, adorned with pearls (whatever else), glimmering round her décolletage, twinkling in her hair and on her snowy robes, starlit and precious. Her message is one equally tinctured with comfort, whispered panaceas and soul-soothing balms. She begins by telling the man that he need not worry about having lost her pearl (alternatively, that the poor father need not grieve his daughter). ‘Sir,’ she says deferentially, ‘Ȝe haf your tale mysetente, / To say your perle is al awaye,’ or: ‘Sir, you have misrepresented your tale / To say that your pearl is forever gone’. She reassures him that his dear pearl is safe and loved. She is actually one of Christ’s ‘vyuez in blysse’ (‘wives in bliss’) and belongs utterly to Him, benefitting directly from His protection and comfort. ‘He gef vus to be His homly hyne / And precious perlez vnto His pay.’ We can translate ‘homly hyne’ almost directly as ‘homely home’, which to us moderns might seem a bit clunky or periphrastic, but it’s not actually a tautology. The online Middle English Compendium by the University of Michigan tells us that ‘hyne’ usually refers to a house of servants, and that the modifier ‘homly’ connotes intimacy, familiarity, safety. Very much the cognate of the modern British usage of ‘homely’—pertaining to the beloved cosiness of home. And what greater comfort than home? The pearl-maiden seeks to comfort the man by telling him, in turn, that she lives in comfort. There’s no place like home, Dorothy repeats with gusto to herself in the backlands of Oz, wishing herself to be back safe in Kansas.

In The Cloud of Unknowing (c. 1390s) (…I lied, this is the last medieval text—but I’ll only talk about it for half a paragraph), the anonymous author seems to delight in bullying their reader, addressing them as ‘weike wreche’. This is a neat sight-translation: ‘weak wretch’. But even this scathing author, reminding us insultingly to ‘see what thou arte’ (ie. not much) and to ‘be more meek’, concedes that we will still ‘be fed with the swetnes [sweetness] of His love’. This is doubly comforting. We will be materially taken care of and we will be loved. Quids in. And this is redolent of the theological philosophy of Matthew, which addresses human anxiety seven centuries before psychologists, armed with their venerable and totalising DSM-5, tried to medicate and therapise humans out of the pathology.

25Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or drink; or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothes? 26 Look at the birds of the air; they do not sow or reap or store away in barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not much more valuable than they? 27 Can any one of you by worrying add a single hour to your life[a]? (Matthew 6: 25-27, Via BibleGateway)

(Benevolently I spared you the Middle English there; the illicit Wycliffe Bible translation of the fourteenth-century, back when translating the Bible out of its customary Latin and into vernacular English was an offence punishable by death.)

That’s religion all over, isn’t it? It’s a source of comfort—or it can be. I once watched a video from an Islamic scholar in which he said something about why he believed in Heaven. I will paraphrase—he argued that even if it turned out somehow that Heaven wasn’t real, he felt more comfort whilst he was alive by choosing to believe that Heaven was real. This was a net gain with immediate results even if he ended up being wrong—because it meant he could live out his earthly days with the belief that he would be rewarded and safe in the afterlife. This reflexively made hardships easier to pass through. Carrot on the stick. With the carrot dangling in front of him, the donkey feels he has something to continue on for, and so he plods on.

It feels like a terminus to quote scripture; religious writing. Maybe it’s because it’s so often about love. Maybe it’s because it’s divinely ordained, supposed to command our lives anyway—supposed to be the ultimate rule-book we consult and supposed to supersede any other book we could read. Quoting gospel triumphs quoting Shakespeare any day.

If I speak in the tongues of men or of angels, but do not have love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. 2 If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. 3 If I give all I possess to the poor and give over my body to hardship that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing. (1 Corinthians 13: 1-3. Via Bible Gateway)

Without love, there is nothing left of us to speak of. However you feel called to love, please do it. And believe in it, too. Write up your own thesis on it. And then defend it. Congratulations, you now have a doctorate in your own theodicy of love.

Keats, John. The Letters of John Keats. England: Reeves & Turner, 1895. (p. 502)

James Baldwin to LIFE Magazine, via: https://www.penguin.co.uk/articles/2021/08/best-james-baldwin-quotes-still-true-relevant-today

Laslett, Peter. The World We Have Lost : Further Explored. London, [England] ; Routledge, 2015. (Originally published in 1965). (p. 29)

From Ancrene Wisse: Part One, Robbins Library Digital Projects. Free online for everyone! Read it! via: https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/text/hasenfrantz-ancrene-wisse-part-one

ugh i'm so glad old english went to good use (i am obsessed)

Superb. Just superb. A wonderful meditation on all the meanings of faith, love, and comfort through the ages. I have little to add but a piling-on of dusty citations dropped from the bookshelf, and an observation that the sensation of God is love. Therein also lies God's real manifestation in the world - love. The core of the Bible (and so many other religious texts): love. It's not for nothing that the Marcionite sect, in the wavering infant days of Christianity, thought that the agapetic, loving God of the New Testament could not possibly be the aged judge of the Old Testament.

But you know, and feel, so much of this already. I suppose I shall just add that I find fascinating just how utterly penetrating this radical love is in Christianity. (Prevalent and penetrating in other faiths, too, I just know them less well.) So many vituperative millenarians, so many preachers with words illumed by Hellish flame, so many stern warriors for faith who were all forced to admit a core of unconditional, true love in faith. Luther, who saw himself as a wretched sinner, admitted that God must have a great and unlimited kindness and grace towards humans to forgive them. Pope Benedictus XVI, that great German conservative, still wrote Deus caritas est. It is the terrifyingly unavoidable thing about faith that we are always loved, whether or not we want it, whether or not we feel we deserve it, whether or not we can see it. It envelops all of us.