Lessons You Learn at a Girls' School

Do we still need single-sex schools for educating our girls?

What is it like inside a boys’ changing room?

Given that I attended a single-sex, all girls’ school, I haven’t a clue. Girls’ changing rooms, however—those I know intimately.

Let me set the scene.

Humid, miasmatical with sweat, and chock-full of too many bodies. Shirts are unbuttoned and shed and sweaters tossed unceremoniously to the floor. The room drones as gossip is disseminated. As a soundscape the room mimics an aviary. Voices ring shriller and higher-pitched than birdsong.

Each girl wears a polo shirt with the school’s crest emblazoned on the right breast. What are you wearing your nicest lingerie to school for? Red lace which is visible, bright and pert, through sheer school blouses. These blouses are somehow always manufactured on the gauzier side of diaphanous. The manufacturing industry is corrupt and depraved. Each girl parks herself in front of a peg on the wall, where she slings her coat and her gym kit and her school bag and maybe her unwieldy art portfolio. There is never sufficient room for anyone and all their miscellaneous belongings, causing sharp elbows to jut into exposed midriffs; ow. The serious netball girls are wearing lycra racerback sports bras, watermarked decisively by brands like Gilly Hicks and Gymshark. Taut girls’ abdomens are bisected by exposed Calvin Klein waistbands.

The insecure girls have devised a method to slip their shorts on underneath their school skirts. Now, this process is slower but some find it more dignified, even as it involves wriggling and shimmying out of their skirts.

As an adjunct, there was always the breed of girls who got changed into their P.E. kits very slowly, deliberately, being in no rush. They revelled in the freedom and privacy offered by the changing-room—away from the hawkish surveillance of their teachers, at liberty to chat idly with their friends or to eat a snack. (Of course, immediately upon producing said snack, other girls would encircle them, begging a scrap like a stray dog, underfed with balding fur.)

These girls were serial offenders and time-wasters. They’d dawdle and only very eventually amble into the gym hall for their PE lesson. Why bother rushing? PE for some girls amounted to ritualistic humiliation. There are those among us who are not and never shall be budding Olympians. PE teachers sometimes seem to relish in persecuting those who lack hand-eye coordination, stamina, speed, or those sweet-natured milksops who lack the vim and vigour necessary to defeat your opponent.

Carelessly, some girls leave their clothes heaped and strewn on the floor, whereas others fold their garments up neatly, stacking them on the bench. The room smells like artificial cherry, eau de drugstore, and ‘BO’ all at once. ‘WHO’S GOT SPRAY?’ someone will always demand, and then promptly outstretch their arms like a scarecrow, requesting to be doused in it like an anointing.

To situate the scene in time, here’s a trick: you can identify which year we are in by which trainers we’re all wearing. We will be wearing whatever was popular last season. Slavishly, the girls will have have saved up their hard-won Saturday job wages or their pocket money to purchase these trainers. Adidas Superstars or Nike Huaraches or Air Forces, maybe. One girl’s got FILA Disruptors—well, yeah, but then again, she always has to be different. ‘Fresh crepes’. Shoes never go unnoticed; sartorially speaking they are just about the most important statement which you can make at school.

Alas, they never stay pristine for very long. The poorer girls hang onto their precious pairs for all that they are worth. Faithfully they wear them until the soles tatter, until heels have ground down the tread and till the laces fray since the plastic aglets have split, and the printed brand-name on the insole has long rubbed into obscurity from sweat and friction.

Teachers are always bellowing at girls for incursions against the dress code, and giving detentions for petty delinquencies, like wearing socks over tights or swapping out scuffed black school shoes for a pear of Vans sneakers on the sly. Sumptuary laws. Many breaches of the dress code will land you sundered in detention. Nails longer than your finger. Nails painted. Makeup, any amount which can be detected. Rolled-up skirts, an ever-shortening hemline. Perhaps your blazer has gone walkabout.

“Nah Miss, I dunno where it is. Swear down I had it this morning.”

Maybe you’ve forgotten your lanyard. Number your days, for this crime is unpardonable. Once the headteacher at my school bought a whistle for the sole purpose of blowing it at the girls guilty of this transgression. It was ear-splittingly loud.

The sports played in girls’ schools can be highly gendered, highly specific. Private schools will offer lacrosse, pole vault, rowing, hockey, horse-riding, even ballet. Anecdotally, it was certainly true that at my school, we were forbidden to play football. My school was an all-girls state comprehensive (ie. free to attend, non-selective) in South East England.

That sounds a bit draconian, forgive me. Football wasn’t forbidden—but it certainly was not part of our curriculum. We never ever played it. Once a week, for our recreational exercise, we had an hour of sport. This sport would either be netball or badminton, varied seasonally by us playing rounders in the summer, and games of dodgeball on the last day of term: that was our lot for P.E.

Anyhow, when it comes to girls’ schools, regardless of what or who you are imagining, if you’re imagining schoolgirls clad in miniscule pleated skirts, carry on. You’re doing that part correctly. (Pervert.)

To better understand what people my age feel about their experiences at single-sex schools, I compiled a survey. The survey in question was latterly distributed to my Instagram followers (some of whom attended the same school as me, though not all).

One of the first questions posed to the participants was:

‘On average, whilst attending a single-sex school, how often were you aware that the opposite sex was absent?’

And the results were:

The response to this question was surprising. See, I had always thought that girls would have been tormented by the absence of their male counterparts—and vice versa, reciprocally. On the contrary, NO ONE said ‘I thought about it in every lesson or multiple times a day’. Which means that, according to this survey, no one was glancing over their shoulder at the chair next to them in English class, wishing desperately that it was filled by a friendly specimen of the opposite sex with whom to flirt. Perhaps I have forgotten the comparative joys of sitting next to one of your best friends in a lesson. How you stifle your laughter and try not to make eye-contact (triggering further uncontrollable episodes of laughter) lest one of you is sent out of the room for being disruptive.

I followed this question up by asking:

‘Were you bothered or frustrated by the fact that you went to a single-sex school? Did you feel that you were missing out?’

Respondents again rallied.

One declared: ‘I felt that at a young age not interacting with those of the opposite sex could have impeded people’s social skills. Those that didn’t have friends [of the opposite sex] from primary or outside of school were at a disadvantage. I personally was frustrated at times when I saw my friends at co ed school create life long bonds with the opposite gender that I was not able to have.’ By shutting out half of the population, you are thus halving the pool of people you are exposed to—immediately the number and variety of friendships possible for you dwindles.

Another respondent said: ‘Yeah, especially as a gay student (and later NB) - it felt like an incredibly toxic and oppressive environment and made being gay /queer awful.’ Would it have been easier to have grown up and grown into comfort with an LGBTQIA+ identity within a mixed-school?—far from being a safe haven of homosociality.

Conversely though, a further respondent articulated their partial relief at having attended a girls’ school: ‘It also helped I didn't have to see couples in hallways [...] It meant most of the issues faced at school were solely to do with friendships and school work, there was no awkwardness or pressure around interacting with boys or rumours about dating etc., though I think girls’ only schools come with their own drama.’

Another respondent did not mince matters, though. ‘Yes cos I wanted a man’—fabulous candour here. This was, moreover, the sentiment which I had most anticipated (although whether this betrayed a narrow-minded prejudice towards my fellow girls, I am unsure). Similarly, a respondent who also would have preferred to attend a mixed school claimed that they ‘frequently felt [they were] missing out. In retrospect, I wish there was an easier option for me to attend a mixed school (i.e. there should have been a mixed school in the catchment area)’ Curiously, here, the fact that they attended a single-sex school appears to be one of situational necessity. There had been no other feasible option for them.

And a further respondent debated their response, acknowledging that they had been somewhat frustrated by attending a mixed school, whilst diplomatically highlighting some advantages to the experience as well. ‘To some degree yes, but it mainly bothered me that I knew the segregation wasn’t good for my mental health in some ways. In other ways, it was quite relieving that I didn’t have to look nice for boys so my appearance mattered less. However I know that this was overall negative because it reinforced segregation and the strange power dynamics that come with that. I didn’t know how to view men, unless if they were gay, as actual people rather than objects of desire.’

This last comment serves as a neat segue; germanely ushering in my next point. Whilst it might frustrate some girls to have been withheld from interacting with boys whilst on the school premises, one convincing argument for preserving single-sex schools is that they offer our girls safety and protection.

Potentially, an environment entirely tailored towards young girls allows them to learn in peace, without unwanted male attention. The main focus of a girls’ school is the education of girls. Well, yes—surely! Of course the focus of a school is education! Distractions are eliminated: there is no competition for a mate; only the competition to be the smartest. A girls’ school is designed to be foremostly an educational environment—it permits no inter-sex socialisation. And isn’t that a positive thing? It reduces the chance of sexual harassment or assault—although this is not to say that a female classmate cannot be a perpetrator, to say nothing of a teacher. It means her focus is less likely to stray onto a boy; her preoccupation should in theory be her schoolwork.

One respondent to my survey presented a strong case in favour of single-sex schools for this very reason: ‘Also, as [my school] was a girls’ school with primarily female teachers - where your achievements were celebrated regardless of gender (being the highest achieving *person* in a class rather than highest achieving *girl* in the class) - it felt almost like a mini feminist utopia; it was only upon leaving school that the harsh reality hit!’ Isn’t that precisely the sort of experience we would want—for ourselves, for our daughters?

Arguably, the way a school is sexed is immaterial so long as the school achieves the goal of quality educational provision. Equally as importantly, though, a school must also prioritise the pastoral care of its students. Many incidences of child abuse or domestic unrest are only identified through schools: their responsibility exceeds merely creating literate and numerate citizens.

Our schools should, above all else, be safe and welcoming—for all of our children and young people.

Tangentially, I saw this wonderful video from the user @aview.fromabridge on Instagram. I do encourage you to watch it yourself, but for the time-poor or recalcitrant among us I shall include a snippet of the transcript below. For context, the following is spoken by three boys who are handed a microphone and the opportunity to give a short speech on a topic of their choice, something affecting their lives or bearing on their minds. The boys are aged in their middle teenage years, I’d say.

‘There’s not much to do around here, this is the canal path, we come fishing sometimes, chill out here with a spliff on, catch a couple carp, eat a bit of snacks, sorted. Obviously the youth clubs got all shut down and obviously anything we try to do […] we get taken off […] it’s not necessarily naughty things in a way or bad things it’s just obviously kids being kids […] we get nagged at, the police try to stop us […] literally all we want is a field to chill out on, man […] if you don’t really have mates then you don’t really have nothing to do.’

I don’t include this to posit that defunding youth clubs directly birthed a crisis amongst men or suggest any over-simplified ontology of the crisis. There were many ill-omened variables at play in our culture which have nudged us towards where we are today. In the same breath, I don’t mean to promulgate the old argument that ‘white working class boys are the most discriminated against in the U.K.’—or anything like that. That argument is the favourite child of any right-leaning talk-show or podcast here. The argument itself has has some validity—the U.K. Parliament even decided to look into it: the idea that this subsection of society had been ‘forgotten’.

However, importantly, Parliament’s inquiry did not adjust for sex. What they investigated was the broader category of white working-class, rather than white working-class boys. Are both our girls and boys doing equally poorly?

The independent advisory group SecEd comments that:

Of course, it is true that white British pupils perform slightly better, on average, than BAME children. But, because girls perform significantly better on average than boys, and pupils who are not eligible for FSM perform significantly better on average than pupils who are, then white boys eligible for FSM perform markedly worse than pupils from every other category, including FSM pupils from every other ethnicity.1

The argument that white working-class students are doing especially poorly at school is, one might feel, often used in defence of anti-immigration rhetoric. The claim propounds and emphasises the idea that uplifting those of a non-white, non-British ethnic background comes directly at the detriment of the white British person’s livelihood. It involves striking all the same chords which form the familiar spiel that immigrants come bustling over to steal our [British people’s] jobs and houses and mooch some free healthcare while they’re at it, too.

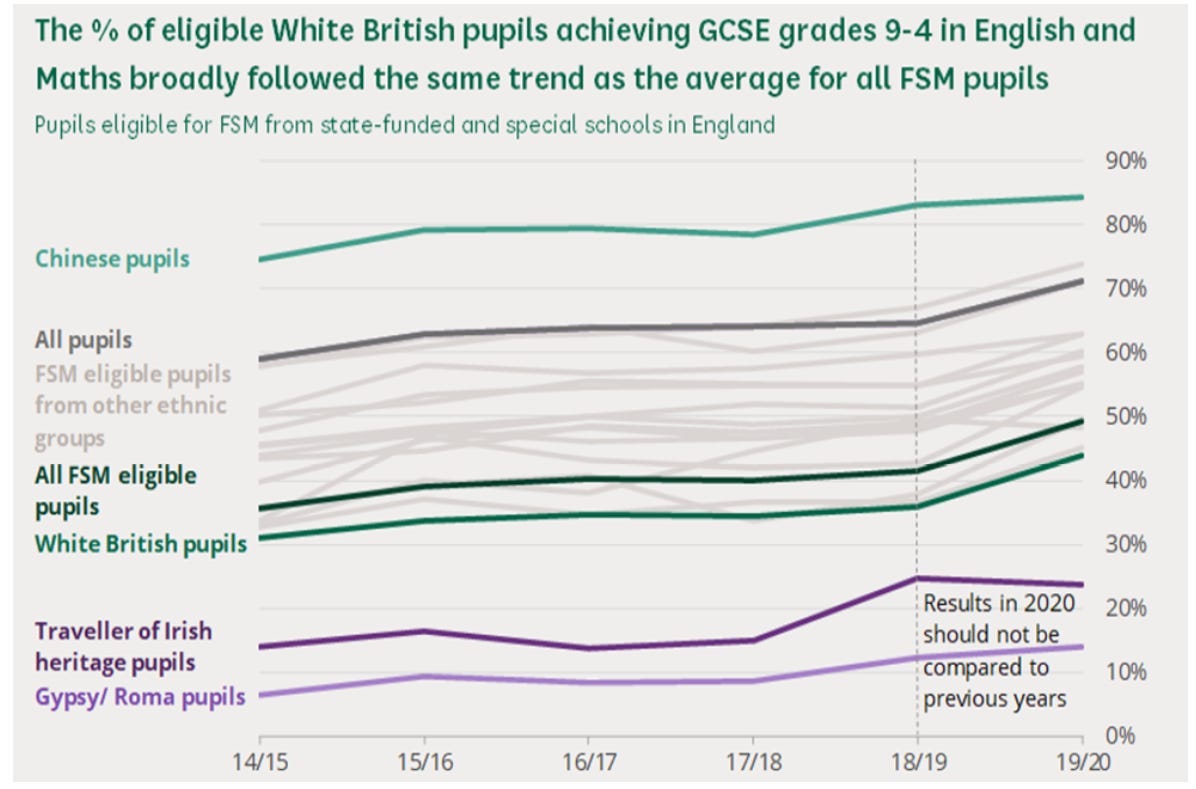

*nb. for graph below: ‘FSM’ = ‘Free School Meals’ - ie. the students eligible for meals being provided by the state; students identified as being in some way disadvantaged.

If we take the authority of the graph (and who among us dare threaten anarchy and brazenly question it?), then yes, it would seem there is indeed a gaping attainment gap between white working-class (or, in this case, FSM eligible—which I own is not strictly the same thing) pupils and their non-white peers of the same, or largely comparable, socioeconomic background.

Journalist Tim Wigmore, writing for The New Statesman, commented in 2016:

Across England, the white working class performs badly. Overall, just 28 per cent of white children on FSMs get five good GCSEs; the figure drops to 24 per cent when girls are excluded. A white working-class boy is less than half as likely to get five good GCSEs, including the core subjects, as the average student in England, and among white boys the gap between how poor and middle-class pupils do is wider than for any other ethnic background. As Theresa May noted in her first speech as Prime Minister, “If you’re a white, working-class boy, you’re less likely than anybody else in Britain to go to university.”2

Darting back to those straight-talking boys I quoted previously, though—I found their speech touching. Their matter-of-fact delivery was refreshing and heartfelt. One of them had lost their mother as a boy. No wonder he cared so fiercely for his friends; he relayed this information to us with calm and measured honesty. Given this tragedy, no wonder he depended upon their brotherhood, the makeshift family the trio of them had formed. It was how they got by, depending on one another. I think so many of us, regardless of what hardships we each have or have not endured, would attest to the same—that it is the precious communities we cobble together out of the people we love which see us through.

Shut up about the girls a minute. For this begs the question: what is going on inside Britain’s boys’ schools?

Are young boys feeling as safe and supported and loved as we try to make our girls feel? Why do I have a hunch that they do not?

Thinking about the present condition of British manhood more generally, earlier this week, Reform UK political leader Nigel Farage made the following comment (via BBC News):

"Look at business," [Farage] said. "Men are prepared to sacrifice their family lives in order to pursue a career and be successful in a way that fewer women are.

"And those women that do have probably got more of a chance of reaching the top than the blokes."3

The devil’s advocate is waiting in the lobby and requesting a meeting with us. It seems wisest to humour him and let him in. Let’s accept the above assertion as though it were fact for a moment. Let’s accept that men approach their lives differently to women: that their work means more to them and ultimately influences their behaviour in such a way that they would defer marriage until much later in life. Maybe the male love-affair with work is so all-consuming and passionate that it might prevent them from ever entering into a long-term, committed relationship, for fear that it might cause them to rejuggle their lives or compromise their accumulation of wealth.

Why is that? On paper at least, we live in a post-feminist world in which the great bulk of gains towards equality have already been made. Everything required for equality in name is already there, if one were to rifle cursorily through a gender-discrimination lawyer’s bureau. The modern woman enjoys many of the same rights and legal freedoms as men. She is the product of the same society—although here the saying ‘No child has the same two parents’ occurs to me as an apposite analogue… Why, then, do men have different priorities, in a society which supposedly furnishes both sexes with identical contemporary values?

It strikes me that I am not actually arguing for segregating the sexes within our schools.

My prerogative is that every child feels safe at school. It is vitally important that schools are places which children want to be, not necessarily just to get them into a good university. That our schools prime children to become well-adjusted, happy individuals who feel that they are part of a warm community. Productively, then, we must ask: Is safety in school—for our girls—contingent on their school being populated exclusively by other girls?

Schools replicate qualities of the family unit. Think about it: a teacher puts themselves quite literally in loco parentis, improvising the role of parent for the students in their care. It is their professional responsibility to look after children, like doctors swearing the Hippocratic Oath pledge to do no harm and to conserve life.

And just as we have ideas of what a family looks like and how it ought function—how our family operated; what we hope our future families will feel like, so we entertain notions of the type of school we want to send our children to.

We wed ourselves to certain ideals of certain types of school. (Where you have the privilege of choice, that is. If you are under-supplied by your local district with schools, or economically restricted to only one nearby institution, this naturally doesn’t apply.)

Former British Prime Minister David Cameron famously sent his children to state school (for my American readers, this means public school). According to The Daily Mail newspaper, he was the first Conservative leader to do so, thereby making a statement. A publicity stunt, slickly engineered. Everything is politics, especially when you are Prime Minister! It was undoubtedly a posture, but one which I am not going to scrutinise too harshly.

But of course, not any old bog-standard, run-of-the-mill school would suffice. Don’t be ridiculous.

David Cameron and wife Samantha are considering one of London’s best all-girls state secondary schools for daughter Nancy, insisting no one should feel the need to pay for private education.4

One thinks amusedly of what might have happened had the Camerons elected to send their daughter to one of London’s many underfunded, struggling schools instead, rather than one of London’s best-performing schools.

For not all state schools are created equally. (I know and I’m sorry—state the bleeding obvious, Alice.)

To say that you have been state-educated doesn’t necessarily mean you have lacked privilege throughout your schooling. To say that you have been state-educated is no longer to suggest that you have been debarred from certain opportunities traditionally only afforded to students paying privately for their education.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies identifies huge ravines of disparity within the state-school sector itself:

But among the 10% most disadvantaged schools in England, nearly a quarter were assessed by Ofsted to have teaching that ‘requires improvement’ or is ‘inadequate’. In the 10% least disadvantaged schools, by contrast, virtually all teaching was rated ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’.

The current way of allocating pupils to schools disadvantages children from lower-income backgrounds and those in rural areas. The school choice system gives substantial weight to distance in deciding which pupils can access what schools. This pushes up house prices near the most in-demand schools, pricing out those on lower incomes. Meanwhile, children in rural areas have fewer schools to choose from in the first place.5

Now, had the Camerons wanted to make their statement of non-conformity even bolder, they could have persuaded other people to copy them. We might hypothesise that they might have encouraged Cameron’s high-earning, middle-class supporters and coterie to follow suit—to send their own children to a state school. Consequently, we could have witnessed a trend in which all the old-seat Conservatives rushed to get their children places in all the underperforming schools. As a result, this would have prompted increased investment in the sector to improve these schools. I do mean financial investment, yes, but I also mean the investment of interest. If moneyed, educated parents send their children to a particular school, they will want that school to perform well.

This is teetering rather close to sounding like gentrification. And you would be correct to accuse me of this, of apparently sympathising with and vouching for the practice. But progress is seldom straightforward: we do indeed encounter ethical conflicts even when trying to improve people’s lives. What, then, do I mean by this?

Naturally, a parent will take an interest in the school their child attends. What opportunities does this school offer my child? Is there anything I can support the school with to extend and enhance its provision? What skills and experience do I have which might prove useful? Can I volunteer in some capacity? Can I use my connections to better the outcomes for this school’s students? Can I serve as a governor? It is logical to surmise that encouraging affluent parents to become involved with struggling schools, even without them actively funnelling their own wealth into the systems, will improve the culture and provision of the schools. You can become a benefactor.

As a parallel: very often, new home-owners are encouraged to buy the worst house on the best street in order to see the greatest return on their investment. By hiring an architect and drawing up great ambitious plans, and dipping into their savings to implement said plans, the old dilapidated house which nobody wanted and the council hoped to bulldoze and redevelop can be transmogrified into something truly aspirational.

What are your opinions on the private sector, for example? Is it ever fair that the quality of one’s education depends on one’s parents’ wealth? And if you are British, do you think Thatcher was justified in dissolving the majority of grammar schools—or are you glad that in some regions of England, grammar schools remain an option… or, if we’re being realistic, they remain an option if you can afford to tutor your child for the entrance examinations, or your child is a prodigy? What do you think about non-fee-paying independent schools; what do you think about religious-affiliated schools, and where should the line be drawn?

But I’ll be careful, and toe the line meekly, and not go any further. I seem to possess a social conscience but I shan’t go infecting you with one too. Anyway, we can’t be doing away with the whole education system as we know it: we’ll end up just sending our children to homeschool co-ops or kumbaya Steiner schools or Montessori groups led by individuals more qualified to teach yoga than mathematics. Some things must remain.

I asked my survey participants the following question: ‘If you became Prime Minister tomorrow, would you ban single-sex schools?’ It turns out that we have very few despots numbering our ranks:

Just 14.8% asserted that yes, they would ban single-sex schools tomorrow if they had the power to do so. (My darling totalitarians.)

Participants were then prompted to elaborate on their responses.

One defended their decision to outlaw these institutions thus: ‘I think they offer a reduced experience of school. I don’t think they’re necessary with the exception of perhaps a religious argument.’ This was not the only time a religious angle was mentioned from my participants, though no one elaborated further on what they meant by this or how this religious caveat could be explored or applied.

Obviously, religious schools already exist in the United Kingdom. But here we are floating the idea of a reality where no secular single-sex schools remain open at all. This means that parents who would prefer for their daughters not to be educated alongside boys now only have the option of an overtly religious education for their girls. Would conceding this freedom to religious groups enable even further segregation than sex-based segregation alone? Surely this risks producing a state wherein a proportion of pupils are not only withheld from intermixing with the opposite sex—but with anyone from outside their family’s religion as well.

Places of worship exist and so do schools. Should the two institutions be allowed to become mirror-images of each other? Arguably, followers of various religions are encouraged to implement their religious principles in every aspect of their life. But one can show charity and compassion, or whatever other qualities their religion emphasises, wherever they go simply by behaving with that intention. Figuratively, one can make a church of a school—or a mosque, or a synagogue—without literally converting the school (foremostly an educational institution) into a place of worship. I realise as I write this, however, that one could argue that a place of worship is a place of education; spiritual education, if you will. But I remain more convinced by the argument that whilst everyone should be free to worship in their religion, it is in the best interest of our society at large for children of whichever religion to be raised together, cheek by jowl. Surely this promotes tolerance, mutual respect, and community-mindedness? This intermixing is done most efficiently by educating our children in the same classroom. All of this savours of the old conflict of church and state—and where, if ever, there should be overlap.

Now, if one were to replace ‘religion’ here with ‘single-sex’, our arguments grow cloudier. The mutual respect I discuss is applicable in this debate, too. I want our girls to respect the boys that they will later go on to share workplaces, universities, homes and communities with. I want our boys to do the same. If educating two groups side-by-side helps promote this sense of respect, then surely it must be good practice?

Regarding banning single-sex schools, there was also an emphasis on freedom of choice for students, for young girls. Numerous respondents stated that ‘children should be allowed to pick where they want to go to school’ and that liquidising such schools would be ‘overbearing from the government: parents and students should have a choice.’ Again, there were echoes that ‘people should have access to their preferred educational institutions’ and the simple though solid argument that ‘it is nice for people to have the choice.’

Participants were asked were asked whether they chose their school because it was single-sex—for the overwhelming majority, they declared that this was not the reason. There were, supposedly, other attractive features about the school they attended; it just happened to be single-sex.

Here’s some food for thought, so please do feast accordingly. One response to this question suggested that ‘it would be interesting to see based on [the] current climate, as conservatism and traditional roles seem to be becoming more popular again, if people would lean more towards boys and girls being together [as this] would be more appealing to help people socialise and become coupled up and eventually have families that fit a traditional ideal OR if it would lean more towards single sex schools to separate boys and girls so purity is maintained and the individual sexes can be lead into the environments they should be in (women more housewife roles and men more manual labour and breadwinner work roles)’.

Conjecturally, single-sex schools could be used to promote a particular right-wing agenda. On the one hand, we could eliminate them totally and then, in our remaining mixed schools, we could engineer an environment dedicated to generating teenage couples, who are fast-tracked into marriage. Within these schools designed to foster romantic affections between students, girls might be catechised specifically for wifehood, whilst the boys are primed for the work-force.

On the other hand though, if we chose to retain single-sex schools, we might minimise the opportunity for potentially undesirable behaviours amongst our teenagers. Rather, behaviours which are undesirable according to right-wing dicta, or theological values such as pre-marital sex (these two sets of scruples are not the same, though, and I am mindful of this).

However, ironically, the goal sketched out in the initial comment is the same either way. The goal is to inculcate our youth into a certain narrow view of gender and of marriage.

Conclusions were ultimately mixed. One respondent, as aforementioned, believed that single-sex schools ‘offer a reduced experience of school.’ But others testified: ‘I felt (and also recognise in hindsight) much safer and able to focus on education in a single sex environment’ and, likewise, another respondent praised single-sex schools for feeling like ‘a breath of fresh air for those who did not want to deal with the anxiety or everyday life that came with having to “perform” in front of others’, describing a girls’ school as a ‘safe haven’, though also caveating this rather positive judgement with a recognition in parentheses: ‘(not to say that they would always feel like this of course, as girls are also bitches)’. Quite so.

For better or for worse, many of us were once teenage girls.

As I write this, I am struck by the feeling that I want people to know that girls can be hungry. I know this might strike you as random. All too often, the scripts we explore of f girls and food is one steeped in starvation.

Yet one thing I remember from school is that girls love food and they love sharing it too. I remember randomly, mid-lesson, girls would turn back in their desks and swivel on their chairs and hiss: ‘Have you got any food?’ This alarum sounding, other girls would rootle in their bags and fish out a lump of partially melted choc or a sling over a packet of crisps. After school, like gannets, reams of girls shall stream into the local shop and pool their loose change to knock up a feast. In my experience, girls love eating together, even the ones for whom food has represented a threat in the past.

Again, similarly, in a girls’ school you shall never want. If you need something, someone will always have it.

Between the jumble of girls, there will always be a dealer, a purveyor. Do you need a hair tie? A pad? A plaster? Hand gel? Tape for an ear-piercing? A pen? A glue-stick? …Always the glue-sticks. No commodity was more greatly in demand than a good glue-stick. If one girl seated at a table of six others had a glue stick in her possession, then no sooner would she produce the contraband but all eyes would be fixed imploringly on her. She might grumble, but she’d duly hand it round, and together the work would get done. Annotated diagrams of flower stems or human lungs would be neatly stuck into exercise books.

Girls’ schools almost resemble an ad hoc welfare state.

What I mean is that someone’s backpack will always be over-supplied. Out of one girl’s surfeit, another girl will be fed and taken care of. It’s hard to fall under the radar, to slip through the cracks. What I am saying is that if you need looking after, you can trust that someone will rise to the task and take you under their wing.

Moreover, homage must be paid to the mothers behind-the-scenes. I can think of so many mothers I know who helped raise other people’s daughters: who fed them after school, took them shopping when they took out their own children, kept an open-door policy—their home was always open.

I want people to know that, certainly so far as my school was anything to go by, the most popular subjects were not stereotypically feminine. The most popular subjects were History, Philosophy, Politics, and Psychology.

This is not to say that ready to be plucked out of the legions of girls enrolled in a single-sex school, a future cohort of Angela Merkels and Margaret Thatchers and Hilary Clintons and maybe even a precious few Jacinda Arderns or Sanne Marins lie waiting to emerge, like larvae, matriarchs in utero.

One also must contribute another observation: was the relative popularity of these subjects due to the fact that they were frequently convened by male teachers?

For of course, it was impossible to expurgate an all-girls school of all traces of the male. The cloister was not entirely enclosed from the menfolk. And if you were a young and dashing male teacher, mightn’t you be quite taken with the idea of teaching in a girls’ school..? Who could blame the poor sods? Those neglected girls need some degree of firm male leadership, after all!

When you dangle a male teacher in front of a classroom of girls, it suddenly becomes apparent how things might have been otherwise, once the core dynamics of an environment are altered. Restructures in the permaculture. One can judge how the girls’ behaviour grows self-conscious and slightly preening, titivating themselves; how it is calculatedly modified and begins to incline towards the coquettish.

But then again, it’s not always about the men. I distinctly remember one girl in History class unbuttoning her shirt and exposing her bra, just to gauge the general consensus of the back of the classroom. Then promptly stuffing it all away again, satisfied with her feedback.

Reflexively, there is also the argument that girls’ schools are overly prudish.

There was a boys’ school stationed just round the corner from our school. But we spent our seven years of education pretending the boys’ school didn’t exist—even though you could spy it from our classroom windows like a fairytale castle over yonder. (Except much more ugly and utilitarian in its architecture.)

There was never any intercourse (hah, droll) between the schools—no shared learning, no pooling of resources, no mixed days out, no initiative, no nothing. I know other single-sex schools would have had nearby partner schools of the opposite sex whom senior leadership encouraged cooperation with, but it isn’t always the case.

And where this is not done—this seems to indicate a missed opportunity. Collaboration typically makes schools—or any institution!—stronger. There must have been some ideological opposition from above, from the governors, from the headteachers.

Anyhow, we girls proceeded as if the boys were not there, and they did the very same.

Both schools’ proms were notably devoid of the opposite sex.

At sixteen years old, a hundred and fifty girls got themselves all dolled up just to dance with each other. They splurged on expensive, Cinderella-esque dresses: layers of crepe and tulle and chiffon. They twisted their ankles in three-inch heels, the stilettoes enfeebled—containing less strength than an osteoporotic spine.

These young and bonny girls dressed up entirely for their adoring parents’ photographs. They dressed upl, I suppose, for themselves: for the best friends that they had grown up alongside in a covenant of sisterhood.

Despite the usual cinematic or televisual portrayal of a prom, there were no men hanging off their arms. For there were no dates at all. Our prom operated on a strict No Plus 1s policy. If, somehow, you had managed to defect from Artemis’s clan of vestal nymphs and had hunted yourself a boyfriend outside of school, then there was no real use in having him, because you couldn’t bring him to show him off.

Retrospectively, observing our prom was a little like watching a dystopian version of the future in which all men had been killed off by some strangely discriminating virus. Alas, so many young and gorgeous girls, and no one there to admire them; to love them! They shall all die unwed and alone.

But at the time, though, I think we were just happy. Perhaps I was oblivious, but I don’t know how much anyone noticed that something so major was missing?

And I can guarantee that there would have been no shortage of love shared and professed that night. It hardly needs mentioning, but as anyone who has ever spent time in a girls’ bathroom will know—women are quick to shower each other in affection. Compliments are a free currency. There are no tariffs nor levies. Girls are pillowy and tactile: hugs, kisses, falling asleep on one another. Anything goes.

Ultimately, I think girls’ schools do a decent job in looking after our girls. They are imperfect. Whilst they champion teenage girls’ especial vulnerability by attempting to minimise threats of sexual abuse or the preoccupying insecurities which can be provoked from inhabiting an environment which invites the prowling male gaze, there remain circumstantially raised risks. Male teachers may seize upon these schools as territorial gains, understanding their own value as a man in a mostly female environ. They are imperfect also in that they do not give our girls a representative experience of the real world by shunting away fifty percent of it. Whilst trying to reduce girlish anxiety around boys, they may actually be augmenting it.

I delegate some further airtime to my survey respondents. I asked them whether they suspected that they might have had a better experience at a single-sex school.

One respondent prevaricated slightly, but ultimately reflected: ‘I’m unsure about having a better experience, but certainly a more well-rounded one.I don’t think it gave me an opportunity to see the full spectrum of the teenage experience—perhaps this is a good thing, though I would have liked to have been able to decide for myself.’ Another respondent also felt that they had been somewhat blinkered or limited by lacking exposure to the opposite sex: ‘I think having different opinions and experiences would’ve benefited my school, including different sexes. I think my school was in its own bubble in a way, it felt quite sheltered from differing opinions.’ The toss-up is whether this shelter is one of true and responsible safety—or one of overmuch caution.

Coda: Lovers on the bus.

These days I notice it everywhere. It is too beautiful to ignore. The freshest, sweetest young lovebirds. My books lie unread upon my shelf, quite disrespected and quite fed up. But I find that all the entertainment I might want plays out before me in the real world.

It seems I inhabit a world seemingly populated with Romeos and Juliets. Maybe it is just Spring.

He and she race each other to catch the bus. She is doubled over and panting by the time they hail it over; he had intended to let her win but a boyish bid for competition saw him lurch into a sprint at the last block. Unable to suppress a grin, they stagger onboard, politely presenting their bus-passes to the driver who nods them through. He is all but expressionless—it has been a long and thankless day—but for the tiniest quirk of his lips, an embryonic smile.

The boy rugby-tackles her: he does so just detectably more gently than he would do to his best friend or his brother. Horseplay—whilst remembering that one spars with a diamond. She is laughing without a pause for breath. They look unspoilt and casual: her school shirt untucked and flapping loose, grass stains smudged on her white socks. Both have abandoned their blazers; his knotted round his waist and she has actually forgotten the whereabouts of hers (she mislaid it on the school field a couple of hours ago, when they were using it as a blanket to lie upon, skipping last period.) Meanwhile his shirt sleeves are rolled up to his elbows, and he is carrying her textbooks for her and only very infinitesimally compromises his gallantry by giving her a thwack on the upper arm with them.

Eventually they quieten like children scolded. An elderly gentleman heaves himself to his bunioned feet (impeccably dressed even at eighty-eight; his hooves are stuffed into a pair of polished moccasins) and gets off the bus. He is all tremors and determination, gripping the handrails until the nodules of his knuckles whiten; his departure frees up a pair of seats. Clambering into them, she lies her head snugly on his shoulder. I always marvel at this magisterial carpentry of bodies, the original puzzle-pieces: the curvature and divots of his shape cushion her well. Absent-mindedly he winds a strand of her loose hair round and round his finger, like a fairy’s helter-skelter. A thing to do occurs to him: he leans over and plants a kiss upon her exposed forehead, heedless of the coarse acne scarring. Look, he can be pleasant and attentive too. The brawling lion tamed.

They do this every day, travelling to and from school. This joy was precipitated by months of rumours—but when confronted about it, there were insistent assertions from the both of them: ‘We’re just friends. Stop it.’ But the rumours abounded anyhow: those salacious breathy whispers which trickle right into your ear in the corridor whilst you queue up for class; meanwhile the slackers ask if there was any homework (bit late to find out now, though, isn’t it?) and some nitwit decides to make a passing Year 7 cry and call her backpack ugly (said Year 7 was already having a wobble because she was running late to second period and she’s never been late before and she absolutely cannot be late).

I didn’t see this at school. I didn’t know of it: how soft and beautiful sapling young love was. There weren’t relationships like this at school. There were a smattering of lesbian partnerships but they were usually quiet, reserved, and unfortunately they kept themselves to themselves, brushed under the radar. But I had regarded the lack of relationships—with a modicum of propriety—as a beneficial thing. Again, harping on that stale argument that schools are not to be used as marriage-markets: that boys are not to gleefully run circles round their harems like baby sultans.

And the romantic in me asks: how can we strive to outlaw from our schools a distraction so sweet as young love?

But shush. That’s off the record.

Bromley, Matt. 5 January 2021. ‘Supporting the education of white working class boys’, Sec Ed, https://www.sec-ed.co.uk/content/best-practice/supporting-the-education-of-white-working-class-boys

Wigmore, Tim. 20 September 2016. ‘The lost boys: how the white working class got left behind’, New Statesman, https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2016/09/the-lost-boys-how-the-white-working-class-got-left-behind

Forsyth, Alex and Joshua Nevett. 27 March 2025. ‘Nigel Farage says men make sacrifices many women don't for jobs’, BBC News, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c4gpnl0x3w3o

Chapman, James. 17 October 2014. ‘David Cameron to become first Tory MP to send his children to a state school’, Daily Mail, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2796964/cameron-set-tory-pm-send-children-state-secondary-viewing-three-four-schools-wife-samantha.html

Farquharson, Christine, Sandra McNally, and Imran Tahir. 16 August 2022. ‘Education inequalities: Inequality: the IFS Deaton review’, Institute for Fiscal Studies, https://ifs.org.uk/inequality/education-inequalities/

There is a very interesting post to be written from the boys-only school perspective - forgive me for not having contributed to your survey. I think there are some very distinct points to make there! This was a very fun read. If I respond, it will be in the form of my own post.

great to see you back and to read more of your writing! brilliant article, and having spent my time as a boy in mixed schools it was really interesting to read this. the thing i found most fascinating was your description of the girls' tendency to share - not something we really experienced as lads haha